…toward sufficient, affordable, robust, and reliable defense postures

by Charles Knight and Carl Conetta, 01 February 2021 (revised 15 March 2022.)

Nations invest vast sums in armed forces,

But will these assets deliver on their promise to defend the nation against aggression reliably?

Will armed forces provide national defense without contributing to international tension, domestic instability, or economic distress?

These questions remind us that there is more than one way a defense posture can fail – and also that success has multiple dimensions and objectives.

Military Stabilization

Military stabilization requires an appropriate and affordable defense establishment and a sufficient, steadfast, and non-provocative defense posture.

Military structures must also avoid aggravating an existing or potential civil conflict. For countries that have experienced severe ethnic and political strife, the national security apparatus itself must not contribute to centrifugal forces.

Military functions and police functions must avoid politicization. Police functions must not be militarized. The composition of forces should reflect the ethnic composition of the nation as closely as possible.

Full-time, part-time, national, and local forces should be thoroughly integrated and interdependent to ensure control by national civilian authorities even in times of great stress to political consent. Full-time troops should generally serve nationally, while more part-time troops may serve locally.

Appropriate Defense

An appropriate defense establishment is suitable for the particular society it serves. Accordingly, nations should be circumspect about the imitation of foreign military structures, preferring instead to build them according to national character and the skills of their people.

Affordable Defense

An affordable defense will achieve security within their existing resource and demographic constraints. To meet affordability criteria, nations that are confident of their own defensive intent can exploit the structural and operational efficiencies of a defensive orientation. These home-court advantages include the high morale of troops defending home territory, intimate knowledge of the terrain, shorter lines of supply and communication, and the opportunity to prepare the likely combat zones intensively.

The inherent efficiencies of a defensive orientation also make it easier to reconcile the confidence building defense criteria of sufficiency, steadfastness, and non-provocation.

Sufficiency

Sufficiency refers to how well a defense posture matches a threat matrix. The degree of “match” involves both qualitative and quantitative aspects of the threat(s).

A broad review of national objectives is crucial in providing a context for the measure of sufficiency. This process will help specify what is to be protected and set the level of defense or deterrence certainty that a nation wishes to attain. Once objectives are clear, it is possible (although by no means easy) to determine military sufficiency. Without such a process, it is impossible to assess sufficiency: The resulting size and composition of defense forces will remain subject to political whim.

In some cases, states will discover that they cannot hope to afford the highest degree of deterrence with a transparent and assured capability to quickly and efficiently defeat any aggression. This is a common dilemma for many smaller states with larger and more powerful neighbors. However, lesser objectives may be within reach and desirable, for instance, the capacity to substantially raise the cost of any aggression and buy time for diplomatic pressure and supportive intervention from allies.

Steadfastness

A steadfast posture combines the qualities of robustness and reliability. Although, in some sense, encompassed by the notion of sufficiency, “steadfastness” refers to intrinsic (that is, non-relational) aspects of a defense posture. “Integrity” and “cohesion” are approximate synonyms for steadfastness.

Robustness refers to a defense array’s capacity to absorb shock and suffer losses without catastrophic collapse. Instead, the defense maintains a cohesive combat capability. Even when facing an overwhelming threat level, a robust defense force will degrade gracefully, buying time for re-grouping, mobilization of reserves, diplomatic intervention, or outside assistance.

As a general rule, a steadfast and robust military posture will not exhibit an over-reliance on concentrated forces and base areas which provide lucrative targets for an enemy. Nor will it depend on a narrow set of technologies that an enemy can counter through a dedicated innovation and acquisition program.

Reliability is the second aspect of steadfastness. It refers to the military’s capacity to perform as planned with high confidence across a wide variety of environmental circumstances. A reliable defense will avoid the security gamble of high-risk operational plans or dependence on immature or poorly integrated technologies.

Reliability is also a function of social relations in society at large, in the nation’s armed forces, and in its personnel’s motivation and training. A reliable military is motivated and ready to conscientiously serve the state in a role that is understood to be both important and limited.

Non-Provocation and Confidence Building

A defense posture is non-provocative if it:

- embodies little or no capacity for large-scale or surprise cross-border attacks and

- provides few, if any, high-value and vulnerable targets inviting an aggressor’s attack.

These guidelines pertain most strongly to the problem of crisis instability, those periods of rising political tension during which the fear of (and opportunity for) a preemptive attack may precipitate an otherwise avoidable military clash. Beyond crises, a non-provocative posture will affect other nations’ perceptions of threat and, consequently, their defense preparations.

The non-provocation standard also addresses the security dilemma by reducing reliance on offensively-oriented military structures. In so doing, it aims to minimize the threat of aggression inherent in any organized armed force. Such threats often stimulate arms races and countervailing offensive doctrines. Moreover, by bringing military structures into line with defensive political goals, the non-provocation standard facilitates the emergence of trusting, cooperative, and ultimately peaceful political relations among nations.

In contrast, any doctrine and force posture oriented to project power into other countries is provocative unless reliably restrained by political and organizational structures.

The institutionalization of confidence- and security-building measures (CSBMs) can normalize the exchange between states of doctrinal and defense planning information and provide forums for assessing the regional impact of various national defense planning options. Confidence building defenses (CBD) include most types of CSBMs. While CSBMs emphasize communication and procedural matters, confidence building defense pays particular attention to military structures and doctrines and their effect on international confidence and national stability.

Implementation

Implementation of an effective confidence building defense must consider context, international relations, and a process of optimization.

Defense options that minimize interstate tension and distrust should be preferred. Planning must be sensitive to the provocative nature of many military options.

Even forces optimized for defense will retain considerable offensive capability on the tactical level. This offensive capability often represents a security threat for neighboring states and may have strategic significance, especially when extensive power asymmetries exist.

Optimization

The planning problems inherent in the simultaneous objectives of affordability, robustness, reliability, and non-provocation require thoughtful attention to optimization.

Optimization of the application of resources toward achieving objectives should be a goal of any institution. Accordingly, military development policies must consider their effect on the matrix of intra- and international social, political, and economic relations. Only then can military-technical considerations, such as the tactical performance of particular weapons platforms, be understood for what they are: a necessary but insufficient basis for policy optimization.

Weaponry, platform complexes, communications systems, and equipment for transport and field engineering are the principal instruments of military operations. In conditions of limited resources, choosing what combination of military instruments to acquire is critical. However, these decisions are complicated because there is no such thing as a defensive weapon, per se. Every weapon can be used offensively or defensively.

The most effective indicator of military confidence-building is in a nation’s overall military posture, unit compositions, and the accompanying doctrine for employment. Consequently, civilian leadership must be familiar with and be able to articulate both aspects of a confidence-building defense.

~~

Adapted from Carl Conetta, Charles Knight, and Lutz Unterseher, Building Confidence into the Security of Southern Africa, PDA Briefing Report #7. Commonwealth Institute, 1996. https://www.comw.org/pda/sa-fin5.htm (accessed 17 January 2021)

~~

➪ PDF version

depend on that rationality and restraint? Probably not.

depend on that rationality and restraint? Probably not.

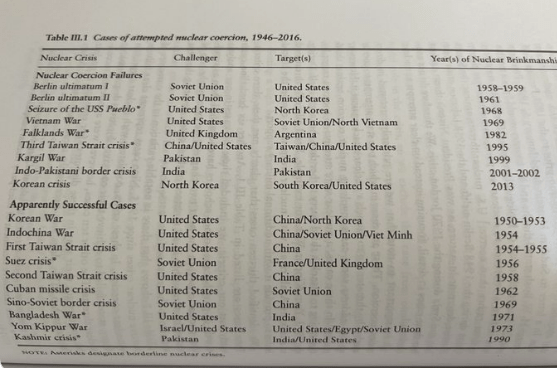

Theoretically, for an effective and stable mutual nuclear deterrent, a credible capability must exist to respond to a nuclear attack with an overwhelming retaliatory attack. However, this was not the case for the Soviet Union until the end of the 1950s or the beginning of the 1960s. This meant that the US had about fifteen years following WWII in which it had relatively unrestrained nuclear options and could attempt nuclear coercion or compellence of adversaries without risking devastating retaliation by the target country.

Theoretically, for an effective and stable mutual nuclear deterrent, a credible capability must exist to respond to a nuclear attack with an overwhelming retaliatory attack. However, this was not the case for the Soviet Union until the end of the 1950s or the beginning of the 1960s. This meant that the US had about fifteen years following WWII in which it had relatively unrestrained nuclear options and could attempt nuclear coercion or compellence of adversaries without risking devastating retaliation by the target country.

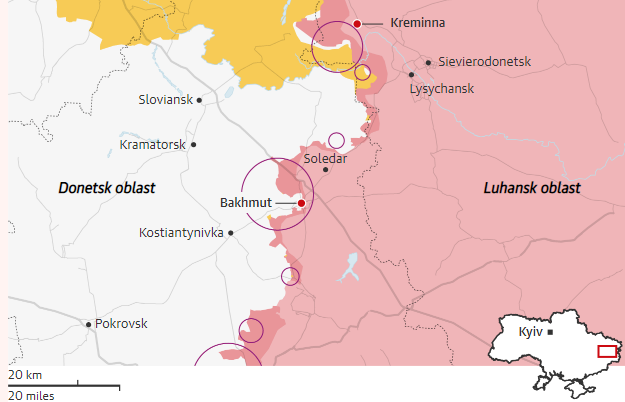

The basic elements of a solution to the Ukraine crisis are ready at hand – and have been since Feb 2015. These are the provisions of the Minsk II Protocol. This

The basic elements of a solution to the Ukraine crisis are ready at hand – and have been since Feb 2015. These are the provisions of the Minsk II Protocol. This

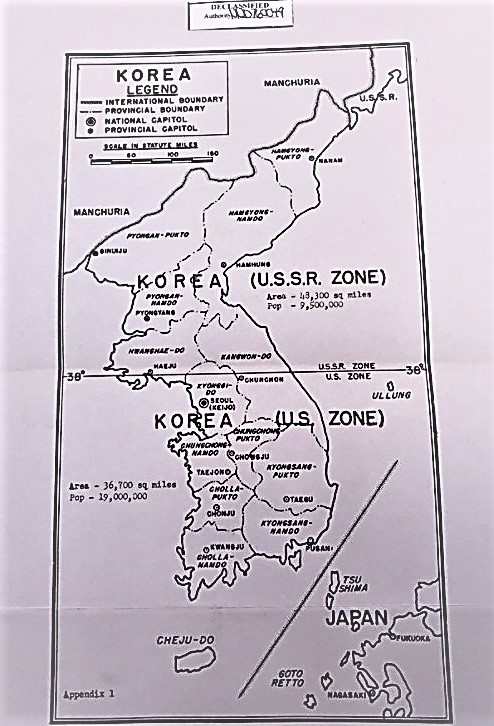

The April 27, 2018 Inter-Korean Summit was a visibly cordial event. At its conclusion, North and South Korea released a Declaration of Peace, Prosperity, and Unification. This paper reviews a selection of key sections and phrases in ‘The Declaration’ with attention to understanding their implications for the goal declared by both parties of ending ‘division and confrontation’ on the peninsula and for addressing the overhanging issue of denuclearization. Notably, both parties strongly assert their rights as Koreans to take leadership in this task.

The April 27, 2018 Inter-Korean Summit was a visibly cordial event. At its conclusion, North and South Korea released a Declaration of Peace, Prosperity, and Unification. This paper reviews a selection of key sections and phrases in ‘The Declaration’ with attention to understanding their implications for the goal declared by both parties of ending ‘division and confrontation’ on the peninsula and for addressing the overhanging issue of denuclearization. Notably, both parties strongly assert their rights as Koreans to take leadership in this task.

The most serious deficit of the Afghan National Security Forces…is its lack of motivation in comparison to the Taliban. One of the primary lessons unlearned from Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan is that soldiers in the armies we create, train, and equip are simply not willing to fight and die for weak, corrupt, illegitimate governments.

The most serious deficit of the Afghan National Security Forces…is its lack of motivation in comparison to the Taliban. One of the primary lessons unlearned from Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan is that soldiers in the armies we create, train, and equip are simply not willing to fight and die for weak, corrupt, illegitimate governments.