Can the United States escape the vortex of its 20-year war?

Carl Conetta, Project on Defense Alternatives, 09 Sept 2021

Carl Conetta, Project on Defense Alternatives, 09 Sept 2021

15 August 2021- in short order, a 20-year $1.2 trillion US effort at nation-building evaporated, disintegrated, went up in smoke. And while unreconstructed interventionists pummel President Biden for surrendering Afghanistan, the truth is that we never had it. What we held instead was a hollow construct of our own imagination and creation – a client pseudo-state. And when it was finally and fully tested, it (for the most part) threw down its arms and ran away.

In a sense, the sudden collapse of Kabul’s government and security services provides the surest litmus test of America’s 20-year enterprise in Afghanistan. It tells us that coercive nation-building by a foreign power – indeed, an alien power – is an impossible mission. Outsiders lack the knowledge, indigenous roots, legitimacy, and degree of interest to succeed against local resistance. Their very presence is provocative, especially given differences of language, religion, and culture. It’s as likely to spur resistance as it is to quell it. At the same time, such interventions risk becoming intractable given domestic political dynamics and Washington’s fixation on preserving its superpower reputation, its claim to being the “indispensable power”.

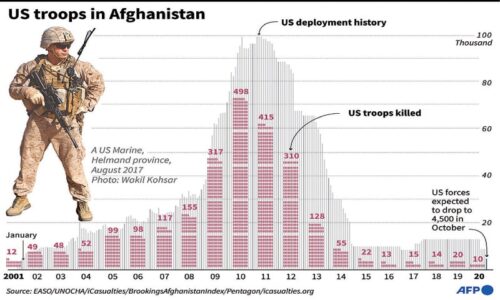

America’s interventionists have had only one answer to the persistence of failure: Stay the Course (with minor adjustments and occasional troop surges). They commonly aver that “Will” is the ingredient lacking in US adventures abroad. Public support or tolerance for this view steadily declined after the completion of the Obama troop surge in 2012; By April 2021 less than one-quarter of Americans would affirm it. However, the deadly mid-August disorder at the Kabul airport has given interventionists a fresh opportunity to assail withdrawal, if only obliquely.

While most Americans have come to accept the need and wisdom of withdrawal, the bloody mess at the airport casts a shadow over its practical implementation. US hawks and interventionists mobilized this impression to challenge the goal of withdrawal itself and to rally opinion to support interventionism – presumably by smarter means. Ostensibly the criticisms concerned the manner of withdrawal, not the fact of it. However, during August, the one type of complaint morphed seamlessly into the other, with interventionists decrying the “abandonment” of the Kabul regime, blaming the collapse of Kabul’s forces on the USA, demanding that American forces secure Kabul province, and ultimately insisting that Biden renege again on a withdrawal pledge and keep troops in Afghanistan until “every American is brought home.”

In recent complaints, there was no proposed new course that credibly promised to deliver the type of Afghanistan that Washington’s nation-builders had sought. And there was little recognition or expressed concern that the proposed action – defer withdrawal – would have involved returning to war with the Taliban. There’s not even much attention to the fact that the Taliban had recently been helping to protect US forces, safely escorting US nationals to the airport, and fighting off ISIS. This degree of cooperation was limited and conditional, but also essential. It should not have been summarily dismissed – especially given that Kabul’s military, such that it was, offered no alternative.

The Biden administration did err seriously in failing to fully appreciate what little progress had been made over 20 years toward building a functional Afghan government and military. How much progress was there? Next to nothing lasting or reliable. Failing to see this is an astonishing omission, but the omission has been endemic among US security policy officials. And it has kept the USA stuck in an impossible mission for 20 years. To be fair, the Biden administration appreciated the short-fall more than most officials, although not nearly enough – hence, the airport fiasco.

Did America’s covey of intelligence agencies “see it coming,” as some critics assert. No. Not usefully. The intelligence estimates that were supposed to guide the withdrawal repeatedly proved to be “an hour late and a dollar short” – that is, not usefully accurate, timely, or detailed:

- In mid-2020, the intelligence consensus had been that the Taliban might triumph within two or three years.

- By 27 April 2021, when President Biden announced the prospective withdrawal date, the intelligence estimate had been revised to 18 months – which, actually, was not much different than the 2020 estimate in terms of the possible end date. Rather reassuring, it would seem, but wrong.

- By 23 June, a possible collapse date was further revised to be as close as 6 months away. US retrograde operations had somehow lost a year of leeway over a period of just 2 months. Still, the projected horizon was still far enough away to allow smooth completion of the planned evacuation. Had it been correct. But it too was wrong.

- A mid-July estimate argued that despite Taliban gains, “the capital is not at imminent risk of a takeover, thanks in part to the threat of US airstrikes.”

- In early August, DOD disseminated a new, foreshortened estimate of possible Taliban victory: 90 days.

- Soon after – around Aug 12 – less than a week before the regime’s collapse – a new intelligence assessment concluded that the Taliban could isolate Kabul within the next 30-to-60 days. Still, room enough to complete withdrawal – but wrong.

Only in late June 2021 did intelligence services begin seeing a possible collapse before the end of the year. And at no point did intelligence services see a potential collapse before mid-September. Rather than aid the administration, this cluster of mistaken estimates may have contributed to the administration’s faulty calculus.

Still, outside the intelligence establishment, there were sufficient sources indicating that the Afghanistan effort was rotten at the core – a patient perpetually on life-support. The Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) saw it, the federal government separately recorded it, the news media widely reported it, and various non-governmental organizations chronicled it. The sorry condition of the effort might also have been gleaned from President Ghani’s January 2018 assessment that the Afghan National Army would not last more than six months without US support and that the Afghan government would also collapse. Thirty months hence, nothing had changed to improve this situation. In fact, Ghani‘s assessment has been shown to be overly optimistic.

The administration’s endgame plan envisioned the Kabul regime minimally securing Kabul Province while holding much of the center and northeast of the country long enough for an orderly US troop withdrawal to occur. Civilian evacuations would continue after the troops’ departure. The long-term survival of the regime was thought to be problematic, but not hopeless. And the Biden administration intended to continue supporting Kabul’s military effort with funds, training, equipment, force planning, munitions, logistics, and intelligence. Direct US military action would occur from “over the horizon,” but only to blunt explicit terrorist threats.

This administration’s program was not much different than how both the Obama and Trump administrations had come to see a possible future end game and post-deployment relationship. What should be the centerpiece of discussion now is that all these expectations stretching back a decade and more were delusional. In that light, Biden’s misjudgments about the near-term reliability of the Kabul regime were just a lesser instance of those guiding US policy for 20 years. This shows the danger of narrowing critical attention to the airport debacle: It produces no caution against the impossible missions, the torrent of hubristic error that culminates in last acts such as this one. Of course, for some critics, preserving the interventionist prerogative takes precedence.

Did Biden’s decision to proceed with withdrawal actually contribute to the collapse of the Kabul government and military, as some critics say? Yes, certainly – how could it not? America’s “Afghanistan” was a client-state, a desperate dependency. A fiction. The USA was its paymaster and superpower partner in war. Once fully tested on its own, it quickly crumbled. That should not be surprising – although much of Washington has acted as blind to this reality for years or tried to suppress it. As the collapse actually unfolded, each local loss or setback suffered by the Afghan National Security Forces added to the momentum of collapse (calling to mind the effect of the German blitzkrieg on the French military in 1940). The rapid desertion of soldiers and politicians from their posts was the impetus for the Kabul airport chaos. But the essential precondition for chaos and collapse was the inherent decrepitude of this foreign-imposed state. Yes, by his action, Biden pulled the curtain back on this fragile corrupted entity. It was weaker than he or the intelligence establishment or most US state managers had expected.

Diplomacy as War by Other Means

Having lost the war, the United States and its allies are now coordinating to win the peace by other coercive means: stopping aid, reviving and stiffening sanctions, blocking recognition, freezing financial assets, and denying the Taliban government access to the global commons. Of course, a wide range of covert means is also available.

The leaders of the G7 countries have warned the Taliban not to revert to the strict Islamic form of government that they ran when they last held power. And the G7 has asserted “that the Taliban will be held accountable for their actions on preventing terrorism, on human rights, in particular, those of women, girls and minorities, and on pursuing an inclusive political settlement in Afghanistan.”

While compromise on some of the G7 demands seems possible, those regarding the form and composition of the Taliban government are unlikely to find any acceptance. The Western alliance straight-out dictating the contours of an Islamic government is a non-starter, to stay the least. The Taliban will not soon or easily surrender the commanding position or core principles for which 50,000 of its members died. While punitive measures might compel a degree of shaky compliance in some areas, the greater effect of tightening the screws on Afghanistan will be instability, hostility, realignment, and missed opportunities for cooperation – in other words, more pain and loss on all sides. The cost-benefit ratio for this campaign of punitive diplomacy is not encouraging, but other dynamics can drive the confrontational approach, nonetheless.

Sanctions, as an assertion of power after losing a war, may speak to the domestic politics and public opinion of the losing states. Punitive measures may also aim to restore some of the reputational heft lost by the United States due to the Afghan war outcome, saying in effect: our destructive power does not end at the edge of the battlefield. Some argue that the reputational fallout of such losses doesn’t matter. That’s wrong, judging from the geopolitics of the immediate post-Vietnam War years. There is a reputational price to pay for imprudent and/or unnecessary military adventures, although the United States obviously recovered its hegemonic prerogatives within 15 years of North Vietnam’s victory.

Finally, the temptation to enact severe sanctions and other punitive measures after a war loss may be intentionally aimed to destabilize Taliban rule and help feed resistance, perhaps reviving war on a proxy basis. In this example, punition would not simply serve as a tool of coercion; It would be meant to actually achieve destabilization and perhaps collapse.

Regardless of motive, the punitive approach undermines rather than enhances regional and national stability. And it feeds contention rather than cooperation. It continues to view Afghanistan and the surrounding region principally through the lens of 9/11 and America’s 20-year war. It literally revives that war and continues it by other means. And it minimizes the regional reality of new actors, new challenges, and new opportunities. A different approach might build on the precedent of selective US-Taliban cooperation achieved over the last two years – transactional for sure, but real nonetheless.

Stabilize Afghanistan: Make Peace with the Taliban Now

As an alternative to pursuing a peremptory approach to the Taliban, Washington should immediately establish a civil, diplomatic modus. It should pursue a non-coercive transactional relationship. This seemingly audacious turn in policy offers the only realistic prospect for moving soon toward a more stable country and region, which will be achieved together or not at all.

A more cooperative relationship might quickly begin to address and advance a variety of important goals:

■ Ensure the return home of all foreign nationals who care to depart Afghanistan as well as releasing all Afghans with travel authorization from another country (as the Taliban have pledged).

■ Preventing or interdicting the export of terrorist influence and activity. Especially, work jointly against ISIS-K.

■ Containing or reducing other transnational criminal activity, especially the drug and arms trades.

■ The development of regional confidence and security-building mechanisms, such as conflict resolution and arms control protocols.

■ The advance of equitable, sustainable economic development.

Other important subjects of cooperation that might begin soon include migration control, environmental protection, and transnational health concerns.

Full and formal normalization of relations will take time, but many aspects of normalization (affecting, for instance, trade and aid) should go forward quickly on a provisional basis. This should have a stabilizing effect on the country and advance cooperation in all spheres.

As suggested above, any attempt to compel Taliban adherence to outside political and social ideals and practices will prove very contentious. But more can be accomplished within a context of cooperative relations than without. And, of course, in the final resort, no nation is compelled to trade with or aid others whose policies it considers abhorrent. (WTO rules give leeway for trade sanctions on a number of non-economic pretexts.) The prospect of limited restrictions argued explicitly on the basis of adhering to one’s own national laws may be a way of favoring change without giving the impression of a united front against the Taliban or an opening shot in a “clash of civilizations.” Neither of these stances would be productive, although possibly gratifying to some.