The short answer is “no” – but there is more to the issue than that. A closer look at the road to war also illuminates paths to a negotiated end.

Carl Conetta, Project on Defense Alternatives, 09 June 2022

Carl Conetta, Project on Defense Alternatives, 09 June 2022

In early May, Politico reported Pope Francis suggesting that “NATO may have caused” the Russian invasion.[1] What the Pope actually said was more cautious and useful in understanding the road to this war. As clarified by Religion News Service, the Pope had suggested that:

“NATO barking at Russia’s doors” may have raised alarms in the Kremlin about the Western European alliance’s intentions in Ukraine. “I can’t say if (Russia’s) anger was provoked,” he continued, “but facilitated, maybe yes.”[2]

Neither NATO nor US policy caused the Ukraine war. The invasion was Moscow’s unforced choice. But that doesn’t settle the issue of provocation. Although neither provocation nor “facilitation” amount to “cause,” such dynamics might have played a role in moving us toward this war. And knowing what role US or NATO policy may have played in bringing the world to this juncture can help illuminate ways to end the conflict (short of prosecuting it to its bitter end – however long that might take and at whatever cost it might entail).[3]

Ivo Daalder, a long-time national security manager for Democratic presidential administrations,[4] rejects outright the idea that NATO expansion had anything at all to do with the February 2022 invasion. He asserts that

“Moscow’s unprovoked aggression is proof that its long-standing complaint about NATO moving too close to its borders was little more than a convenient excuse for its revisionist aims.” [5]

This dismisses the NATO expansion complaint too cavalierly. The author might as well have asserted that because NATO expansion is not provocative, Moscow was not provoked. This argument assumes its conclusion. It doesn’t settle questions about provocation, it elides them.

Does the invasion of Ukraine reflect “revisionist aims” in whole or part? Moscow certainly has sought to inhibit or block Ukraine’s approach to NATO, which became a Ukrainian constitutional imperative in 2019.[6] Restoring Ukraine to the status of a neutral buffer state counts as a revisionist aim, although this instance of revisionism directly reflects concerns about NATO expansion. It’s not a counter-point.

The comparative roles of NATO expansion and independent “revisionist aims” in effecting Moscow’s aggression is a pivotal issue. It bears on the prospect of negotiating an end to this war any time soon. Are we in fact witnessing a first or major step in a dedicated Russian effort to re-establish an empire in the post-Soviet space and overturn Europe’s post-Cold War order by force or coercion?[7] Such ambitions would seem almost Hitler-ite or Napoleonic in character. If so, it might require a protracted war and total strategic defeat to quell Moscow’s will to conquest, regardless of how costly such a war might be. Conversely, if Russian actions have been significantly shaped by an accumulation of more specific issues, incidents, and complaints then the room for productive negotiation is greater.

Although efforts toward a negotiated settlement are presently stalled, this could soon change should a costly stalemate take hold, as seems likely. Also, the regional and global costs of the conflict are mounting, and this will increase pressure for a diplomatic resolution.[8] Already some European NATO members are working independently to advance diplomatic solutions. [9]

Options for compromise have already been ventilated. Earlier in the war, Kyiv had proposed some measures, including formal neutrality, a return to the status quo 2014, and a 15-year pause in deciding the disposition of Crimea and the Donbas.[10] (On 23 May 2022, Henry Kissinger proposed that Ukraine simply cede the same territory to Russia and be done with it; The proposal mostly sparked strong objections in Ukraine and in the West.)[11] Presently, Pres. Zelensky seems to disfavor negotiations, but also recognizes that these are essential to war termination.[12] He must certainly understand that should Moscow face failure in the east, it will impose even greater, more far reaching destruction on all of Ukraine.

For its part, Moscow had suggested horizontal negotiations in mid-December 2021 when it advanced a series of proposals to revise Russia-NATO security arrangements.[13] Although these were too grand, one-sided, and late in the game to win a serious hearing, they suggested the possibility of pursuing broader Russia-NATO negotiations to facilitate compromise on Ukraine. Even portions of the Minsk agreements could be modified and revisited. (Minsk I, for instance, suggests the prospect of a post-war demilitarized “security zone” extending on both sides of the Russia-Ukraine border monitored by the OSCE.)[14]

Some NATO members are presently pursuing more ambitious war goals having less to do with simply defending Ukraine than with punishing Russia and imposing a strategic defeat on it.[15] Some may have already acted to constrain Kyiv’s efforts toward a negotiated ceasefire.[16]

US Sec of Defense Austin has clarified that America’s ultimate goal is to weaken Russia “to the degree that it can’t do the kinds of things that it has done in invading Ukraine.”[17] It’s hard to imagine what Sec Austin has in mind given that Russia has 900,000 active military personnel and 4,500 ready nuclear warheads, and that the case at hand involves an attack on a contiguous nation rather than some distant target such as Iraq or Syria. Any broad assent in the West to this audacious and risky goal depends on the characterization of Russia as a constitutionally expansionist power, posed to possibly sweep to the Atlantic. Weighing against this interpretation would be any conditional circumstances particular to this conflict that helped shape its occurrence and that might be addressed to truncate it.

Putin’s “grand ambition”

Putin’s ambitions are supposed to be revealed in the long July 2021 article written under his name, “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians.”[18] This offers a biased re-imagining of the historical relationship between Russia and Ukraine.[19] Essentially, it concludes that the citizens of both belong to a broader community that has been torn asunder politically by treachery and error. And he argues that, due to historical and cultural ties, “true sovereignty of Ukraine is possible only in partnership with Russia.” This seems an exceptionally covetous conclusion, even an imperial one[20]. But his policy prescriptions are more modest. He observes:

“Some part of a people…can become aware of itself as a separate nation… How should we treat that? There is only one answer: with respect!” [21]

Still, he asserts that seceding groups have an unquestioned right only to that which they originally brought to the union. “All other territorial acquisitions are subject to discussion, negotiations.” The relevant referent here is Crimea. (Of course, the appropriate time for negotiating the disposition of Crimea was 30-years ago).[22]

The article extends Moscow’s interests to Donbas as well. Putin writes that he increasingly believes that “Kiev simply does not need Donbas.” His reasoning is that Kyiv has refused to proceed with the Minsk accord which promised the only way to peacefully restore the area to Ukraine. Here Putin is being sarcastic. Of course, Kyiv seeks to re-integrate the rebel areas – but only on its own terms, not the rebels’.

With regard to both Crimea and Donbas, the article also re-asserts a Russian responsibility to protect the rights of ethnic Russian communities.[23] This issue is especially salient for Moscow because it reflects on the legitimacy of a state espousing a nationalist ideology. Indeed, the article principally stands as an appeal to Russian nationalism, including that allegedly felt by Ukraine’s ethnic Russian community. All of the article’s historical bias is bent to this purpose – a rationalization to build support for the war.[24] On the positive side, however, it also suggests a strict limit to Moscow’s European ambitions.

Moscow’s threat to Ukraine is over-determined

Obviously there’s more to the Russian invasion and occupation than simply an effort to preempt NATO membership, although it certainly does that. The seizure of Crimea, for one, is partly motivated by other critical security concerns due to the basing there of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet.[25]

Russian basing rights were challenged in 2008 when following the “Orange Revolution” (2004) the Ukrainian government under Pres. Viktor Yushchenko (2005-2010) declared that Russia’s lease would not be renewed once it expired in 2017. The next president, Viktor Yanukovych, reversed that decision after taking office in 2010.[26] He negotiated a new agreement extending the lease to 2042 in exchange for lower gas prices. (Notably, the presence of a Russian base on Ukrainian territory would have precluded NATO membership.)[27] The decision would probably have been abrogated after Yanukovych was deposed in 2014 and the new Maidan government began to look decisively West.

In March 2022, Russian Col. Gen. Sergei Rudskoi, deputy head of the General Staff, argued that Donbas was key to the entire 2021 invasion. He said that all of Ukraine was targeted (rather than just Donbas) to prevent Kyiv from continuously threatening Donbass.[28] But this is not credible. The Russian operation far exceeded in risk and cost both the requirement and the value of securing Donbas. More likely the aims were to ensure that Ukraine would remain a reliable Russia-NATO buffer of 1000+ km and to keep at least some of Ukraine in Moscow’s orbit given the close economic relationship between Russia and (especially) Ukraine’s east.

In sum, Moscow’s threat to post-Maidan Ukraine was over-determined, partly due to the extent and nature of the change that occurred in 2014 – the ouster of a democratically-elected pro-Russian leader by a western-supported protest movement. Moscow’s threat to Ukraine is exceptional, however. Apart from Ukraine, Moscow’s unilateral Eurasian military interventions over the past 30 years have not much expanded its writ.[29] The Kremlin did gain and still retains virtual control over small slices of Moldova and Georgia (begun as putative peace operations but now sustained supposedly as a matter of protecting ethnic rights.) On balance, however, and measured over 30 years, Russia is a conservative regional hegemon invested in stasis not revisionism. And central to its military activity along its perimeter have been security concerns. [30]

The Issue of “Provocation”

Did US/NATO policy provoke the Russian attack on Ukraine? If by “provoke” one means “cause” as in a chemical reaction, then the answer is “no.” But the actions of one state that affect another can cause sentiments – alarm, fear, suspicion, outrage, disaffection – among the other’s political authorities that shape their perceptions and predispose them to belligerent responses.

Violent responses are allowed by international law in very few and select circumstances, notably: self-defense against armed attack. Russia’s actions in Ukraine fall far short of this standard. And the notion of “preventive attack” – action to preclude a possible future attack – has no standing in international law, although some (including the United States) have advanced this rationale for war.[31]

While most types of provocative actions do not justify an offensive response, all types make them more likely. Even lawful actions bearing on the security of other states can raise the probability of a belligerent response, lawful or not. And the cascading consequences for the global community of a subsequent war may outweigh the immediate issues at stake. Thus, wise leadership would be careful about reducing or crowding the critical security concerns of other powerful nations, especially nuclear ones.[32] Failing to do so is irresponsible – and perhaps fatally so. At minimum, efforts at mitigation or compensatory steps are required. Sometimes peace, stability, and prosperity are best served by seeking alternative approaches.

Two questions can help assess the possible role of Western policy in the slide toward this war. And both may illuminate a road out – short of fighting to the bitter end. First, does NATO expansion in any sense “threaten” Russia? And second, apart from NATO’s 30-year march eastward, what does Moscow see as more immediate provocations – that is, Why act now?

The NATO “threat”

NATO’s eastward expansion “threatens” Russia in the same general sense that the 1962 Soviet deployment of nuclear missiles to Cuba “threatened” the USA. Although the missile deployment didn’t itself constitute an act of violence, nor even announce an intent to do violence, it did involve an immediate and objective decrement in US security by complicating the nation’s strategic calculus.[33] Security managers and analysts often use the word “threat” in this way, meaning an act or development that increases vulnerability to possible acts of violence or coercion. Such “threats”can be said to be potential, indirect, or incipient. (Notably, security managers typically use “threat” in this way to refer to the vulnerabilities of their own homelands or “interests” exclusively.)[34]

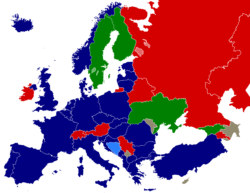

Washington and Moscow have had a long history of contentious relations, never fully repaired. Indeed, NATO was born in opposition to Moscow. It outlasted Soviet collapse, growing from 16 members to 30, incorporating most former members of the Soviets’ “Warsaw Treaty Organization” as well as several former republics of the Soviet Union itself. This Cold War and post-Cold War history is the substrate of present Russian state manger sentiments, perceptions, and assessments.[35]

Since the end of the Cold War, NATO or its leading members have conducted multiple regime-change operations using both non-military and military, covert and open means in Europe and elsewhere.[36] In this light, there is no national leader on earth now or in history who wouldn’t be concerned should a comparable contending military power set-up “shop” next door, especially if done as the nth step in a military “march” of decades.

The close presence of a powerful adversary or strategic competitor constitutes a potential “threat in being,” even though this doesn’t rationalize a violent response.[37]. To compensate in the present case, Russia would have to substantially increase surveillance and defenses along a ~2300-km border. It also would have to attempt compensating for the loss of 1,000-km of defensive depth. Even still, it would be vulnerable to increased cross-border surveillance, espionage, and covert action.

Given that the two sides of the Russia-US/NATO divide hold about 15,000 nuclear weapons between them, it’s wise to keep them separated while developing cooperative means to help ensure the safety of non-aligned buffer states. Ukraine puts 1,000 kilometers between NATO and Russia along its 2,300 kilometer border with Russia. That separation has been a good thing for Europe and the world, although Ukraine has lacked sufficient security guarantees.

Moscow’s complaint

Moscow has been consistently warning and complaining about NATO expansion since Yeltsin’s time [38], having perceived multiple vows that it would not occur [39]. Those complaints grew more urgent in 2004 when former Soviet republics Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania were incorporated. But their borders with Russia extend only 500 kilometers. They are sandwiched between Russian Kaliningrad and Belarus, and connected to NATO via Poland by a narrow corridor of 100 kilometers. The Baltic states have more reason for concern in this case than does Russia.

The next initiative drawing Moscow’s ire was the declaration at NATO’s 2008 Bucharest Summit that Georgia and Ukraine would one day join NATO. Putin, speaking at the summit, immediately warned against admitting Ukraine and moving NATO’s military infrastructure closer to the Russian border.[40] He had offered similar complaints the year before at the 2007 Munich Conference.[41]

By contrast with the summer 2021 article, these presentations focused mostly on security issues – not only NATO expansion, but also NATO’s eastward troop deployments, the collapse of negotiations on adapting the CFE Treaty to new conditions, the unilateral declaration of Kosovo independence, the US withdrawal from the ABM treaty, and America’s increased practice of military intervention. (At the time, the United States had 180,000 troops deployed in Iraq and Afghanistan.)[42] Of course, not long after the 2008 NATO summit, Russia and Georgia went to war with the latter hopelessly outgunned.

In his presentations, Putin’s suggestion of “debts owed Moscow” continued to undergird his appeals for reciprocity. But in this case the putative “debts” relate to Moscow’s “tear down” of the Berlin Wall, its 1989 unilateral reduction of conventional forces in Europe, the release of the east and central European captive nations, and the dissolution of the Soviet Union itself. Outside Moscow these moves were not viewed as “gifts” but as forced choices. Nonetheless, Gorbachev and Yeltsin had risked and won internal disputes on the hope of achieving a common European home.

The long contest over Ukraine

Russia and US/NATO have seriously contended for influence over Ukraine since the early 2000s,[43] but the 2014 Maidan revolution and regime change in Kyiv was a turning point. The Maidan mass movement, supported by the West and representing Western-leaning segments of Ukrainian society, deposed pro-Russia Pres. Viktor Yanukovych, who had won office in a 2010 election (declared fair by OSCE observers).[44] A Feb 2014 peace settlement brokered by the EU between the government and opposition leaders was summarily cast aside on the insistence of Ukrainian Right Sector leaders and some grassroots fighting groups in Kyiv.[45] Weeks later, Moscow seized Crimea.

Moscow rationalized its 2014 seizure of Crimea partially on the basis of a new draft Ukrainian language law limiting the official use of Russian language (later rescinded)[46], the presence of extreme Ukrainian nationalists in the new government [47], and the fact that Crimea’s population was two-thirds ethnic Russian. (The peninsula also heavily favored the deposed President Yanukovych, and a 2014 Pew Center poll found a slim majority favoring the right of regions to secede.)[48] As suggested earlier, Moscow’s principal motivation may have been its strong security interest in maintaining the Black Sea Fleet there.

Earlier in the Maidan revolution, US political support for it had been graphically communicated by photos of Assistant US Secretary of State Victoria Nuland and US Amb Geoffrey Pyatt socializing with the protestors and handing out sandwiches to them.[49] Also, a leaked phone conversation between Nuland and Pyatt revealed them planning to push for the selection of Arseniy Yatsenyuk as next Ukrainian Prime Minister – a position he did attain.[50] As for the EU, the USA was contemptuous of its efforts – or as Nuland put it to Pyatt, “Fuck the EU.” Reasonable people can disagree about what these actions prove about US influence on the events leading to the Feb 2014 revolution, but it is indisputable that such actions would feed suspicions and fears of an improper US role. (Notably, US political and financial support for pro-Western revolutions in Ukraine and elsewhere do not violate international law although they may contravene the non-binding 1981 UN General Assembly “Declaration on the Inadmissibility of Intervention and Interference in the Internal Affairs of States.”)[51]

Donbas and the Minsk protocol

Separatist sentiment in Ukraine’s east grew rapidly in response to the ouster of Viktor Yanukovych, who had strong majority support there, and the rise to power of ethnic-Ukrainian nationalists.[52] When anti-Maidan rebels in the east (who were supported by Moscow) seized portions of the Donbas area in March and April 2014 [53], Kyiv quickly launched an “anti-terrorist” campaign against them.[54] Compromise should have been possible, but from a different perspective, the legitimacy of one rebellion could be viewed as inversely related to the legitimacy of the other. Post-Maidan Kyiv was strongly disinclined to tip its hat in any way to the Donbas rebels.

The Kyiv offensive slowly ground down the rebels until mid-August 2014 when Russian artillery, equipment, and “volunteers” more substantially joined the fight.[55] (Ukraine’s security service estimated rebel strength as 40,000 fighters plus 6,000 Russians.)[56]

Nearly 10,000 Ukrainians died in the first two years of the Donbass fighting (as well as perhaps 400-500 Russians, according to the US State Department).[57] Those first two years of the Donbass fight claimed 75% of the total fatalities through to 2022. The bloodshed slowed from a flood to trickle due to the 2015 Minsk II agreement, mediated by France, Germany, and the OSCE.[58] Average annual fatalities during 2016-2022 were only 10% as great as during 2014-2015.

The agreement provided for a ceasefire; It also entailed granting the rebel areas autonomy within Ukraine. However, while the cease-fire was significantly effective over the next six years, saving thousands of lives, the agreement was never fulfilled. Essential constitutional change never occurred. And autonomy was never implemented.[59]

This was partly due to stiff opposition from ultra-nationalist groups, whose militias had also been vital to the fight in the east. Their fight extended to Kyiv as well. A deadly anti-Minsk II protest by these groups in Sep 2015 involved a grenade assault that left three Ukrainian soldiers dead. (This led Prime Minister Yatsenyuk to say the rightists were “worse” than the eastern separatists.)[60] But the Rada’s governing majority also would not abide by the sequencing of steps set out in the agreement [61] that would have had Donbas elections occur before Kyiv had regained control of the border. The United States among other NATO and EU nations gave vocal support to the Minsk II process, but none applied their ample leverage to compel closure. Their general support for Ukraine vs Russia had put them in a position of moral hazard.

Ukraine’s ultra-nationalist parties and militias have an outsized influence over Ukrainian policy despite their weak electoral showing (seldom as high as ten percent). This is due to their very active memberships (probably exceeding 50,000) and their reliance on mass protest and direct action – sometimes violent.[62]

Relevant to the eastern conflict, their strength was made evident in early 2017 when they blockaded east-west trade routes. During the first few years of the eastern standoff, the rebel and western areas continued a degree of commerce. However, within weeks of the vigilante blockade’s start, government opposition to it melted away and an official blockade was implemented.[63] One predictable result was that the rebel areas integrated more closely with the Russian economy.

Beyond Minsk, Toward NATO

In early 2018, the Ukrainian parliament passed a controversial bill prioritizing the full reintegration of the rebel areas, now defined simply as territory temporarily occupied by Russia as an aggressor state.[64] This supplanted the notion of the struggle as an internal conflict. Soon after, Ukraine replaced the four-year Anti-Terrorism Operation (ATO), which had been led by the state’s security forces, with a Joint Forces Operation (JFO) led by the regular military.[65] On the face of it, these efforts were incompatible with the Minsk agreement. Finally, in early 2021, the Zelensky government openly called for revising the agreement as well as the negotiating body, adding the USA, Canada, and the UK to existing members Germany, France, Russia, and Ukraine.[66] In effect, this was an abrogation of the Minsk agreement and process, although Kyiv said not.

While Minsk II hung in abeyance, the USA and other NATO members began and then redoubled their arming and training of the Ukranian military.[67] NATO and Ukrainian troops also conducted numerous joint exercises both inside Ukraine and elsewhere.[68] As each year passed, Ukraine’s capacity to retake Donbas by force increased.

As for the post-Maidan government’s NATO aspirations: Kyiv had abandoned neutrality and declared for NATO as early as Dec 2014.)[69] In early 2019, it passed a constitutional amendment formally committing the country to becoming a member of both NATO and the European Union.[70]

In 2018, NATO had granted Ukraine official aspiring member status.[71] Finally, in June 2020, it recognized Ukraine as an Enhanced Opportunities Partner.[72]

The view from Moscow

From Moscow’s perspective the progression of events and their meanings would have been clear. An extra-constitutional change of Ukraine’s government in 2014, conspicuously supported by the USA and other Western powers, deposed a democratically-elected Russia-friendly president who was also strongly favored in Ukraine’s east. For Moscow, this could only have redefined the nature of contention over Ukraine.

The change also posed a multifaceted security challenge for Russia involving the disposition of its Black Sea Fleet and the expansion of an exclusionary and competitive military alliance to its borders. When portions of Ukraine’s eastern oblasts rebelled against the change, the Maidan government attempted to forcefully suppress them. Multiple opportunities to achieve compromise in the Ukraine disputes were cast aside (2014 EU sponsored agreement) or held in abeyance (Minsk II) while the country muscled up, deepened its NATO partnership, increased NATO presence, and crept steadily closer to official membership.

None of the above justifies Russia’s illegal actions but it should be clear how these developments might prompt sentiments, perceptions, and assessments that made an aggressive Russian response more likely. Notably, it is not NATO expansion alone that had this effect, but expansion together with the other developments summarized above.

The above analysis reveals multiple opportunities and options for avoiding war by giving some credence to Moscow’s concerns, even though there was no legal compulsion to do so. The draft US-Russia security agreements that Moscow advanced in mid-December 2021 also provided some last-minute opportunity to avert war. Although these served more as a litmus to rationalize war, a positive US response could have forestalled that outcome. None was forthcoming, however.[73]

Principles and Prospects

Moscow frames its case against ongoing NATO expansion in terms of a principle of “indivisible security,” which was most recently set out in the 1999 OSCE Charter for European Security.[74] For Moscow, the relevant guideline is “States will not strengthen their security at the expense of other States.”[75] By its reading, both NATO and its prospective members are aiming to improve their security in ways that diminishes Moscow’s. There is no objective measure by which to determine this, however – and no formal means for adjudicating it. Resolution depends on strategic empathy.

For its part, the United States has repeatedly asserted NATO’s so-called “open door” policy as a reason for standing firm regarding Ukraine’s candidacy. Nonetheless, NATO’s charter and practice reveal several relevant conditions that might shut the door on some aspirants. Notably, aspiring members need first to resolve ongoing conflicts, and their joining the alliance should bring greater security to the whole (and presumably not greater security challenges).[76] Regardless of talk about inviolable principles, no one should doubt that the United States together with other leading members could close the door should they decide that doing so best serves their security, alliance functionality, and/or regional stability.[77] Article 10 of the 1949 North Atlantic Treaty is clearly conditional – and not solely with reference to the character and strength of aspiring members.[78] So why act as though the USA and other NATO members have no choice?

Kyiv has based its plea for defensive support on “the sovereign equality of nations” – a principle enshrined in the UN charter and foundational to all international law.[79] There’s no question that Russia’s assault on Ukraine is a grave violation of its sovereignty. How to productively address this is the present challenge. What if restoration of the status quo ante bellum (pre-2014) is judged unattainable? Or, what if the costs of attaining it are judged too steep – considering not only battlefield costs, but also global costs in multiple registers?

As noted above, various options for compromise have already been ventilated. All would involve a concession to power, however – which is presently the price of stabilization. But as part of any compromise package, Russia could be made to pay substantial reparations (by whatever name) to Ukraine, which would help dissuade future Russian aggression. And embedding compromise on the war within some new and broader Russia-NATO security arrangement could incentivize adherence. Indeed, opening a dialog on an improved European security architecture would encourage Moscow to abandon maximalist aims regarding Ukraine.

Diplomatic progress toward ending the war requires a recognition that Russia’s security concerns have been at least partially legitimate, even though its invasion of Ukraine is not. As NATO leader, the United States is best positioned to encourage and initiate effective East-West dialog on the war and broader security issues. This is not likely to occur, however, because US leaders seem strongly committed to the ultimate aim of “weakening” Russia. Realistically, initiative for compromise will have to be independent, coming first from the UN, EU, OSCE, or all three.

NOTES

1. “Pope says NATO may have caused Russia’s invasion of Ukraine,” Politico, 03 May 2022.

2.“Pope Francis says NATO, ‘barking at Russia’s door,’ shares blame for Ukraine,” Religion News Service, 03 May 2022.

3. Weighing NATO expansion

- “NATO and the Road Not Taken,” Boston Review, 16 Mar 2022.

- “Was NATO Enlargement a Mistake?” Foreign Affairs (19 Apr 2022)

4. Daalder served on President Clinton’s National Security Council. He also served the Obama administration as US Permanent Representative to NATO from May 2009 to July 2013.

5. Ivo Daalder, “Let Ukraine In,” The Atlantic, Apr 2022.

6. “Ukraine President Signs Constitutional Amendment On NATO, EU Membership,”

RFE/RL, 19 Feb 2019.

7. Elias Götz, “Russia, the West, and the Ukraine crisis: three contending perspectives,” Contemporary Politics Vol. 22, No. 3 (2016)

8. Regional and global costs of the Russia-Ukraine war

- “War in Ukraine: Twelve disruptions changing the world,” McKinsey & Company, 9 May 2022

- “Ukraine war to cause biggest price shock in 50 years – World Bank,” BBC, 26 Apr 2022.

- “Ukraine’s Reconstruction To Require Sums ‘Beyond Imagination,’ Says EIB Head,” Eurasia Review, 24 Apr 2022.

- “From soaring food prices to social unrest, the fallout from the Russia-Ukraine war could be immense,” CNBC, 21 Apr 2022.

- “Crisis in Ukraine could slash global trade growth by half in 2022: WTO,” Business Standard, 01 Apr 2022.

- “Ukraine War to Compound Hunger, Poverty in Africa, Experts Say,” VOA, 19 Mar 2022.

9. “Europe’s leaders fall out of key on Ukraine. Germany, France and Italy are making overtures to Moscow,” Politico.eu, 16 May 2022.

10. Kyiv proposed compromises

- “Zelensky floats possible Putin compromises,” Axios, 22 Mar 2022.

- “Ukraine is willing to compromise on Donbass to end war: Zelensky,” NY Post, 27 Mar 2022.

11. Kissinger Davos speech and proposal

- “Kissinger: These are the main geopolitical challenges facing the world right now,” full text, World Economic Forum, 23 May 2022.

- “The War in Ukraine Can Be Over If the US Wants It,” New York Magazine Intelligencer, 1 June 2022.

- Daniel R. DePetris, “Does Henry Kissinger Have a Point on Ukraine?” Newsweek, 27 May 2022.

12. Kyiv takes firmer stance

- “With Ukraine Taking Firmer Stance, Peace Talks Grind to a Halt,” NYT, 17 May 2022.

- “Ukraine peace deal: Kyiv rules out ceding land to Russia,” BBC, 22 May 2022.

13. Moscow security proposals

The two Russian documents proposed (among other things) that:

– NATO expansion end,

– NATO and Russia rollback their European military deployments to the status quo 27 May 1997,

– Neither side deploy land-based intermediate- or short-range missiles in areas that put them in reach of the other’s territory,

– NATO conduct no exercise in Ukraine and none in the other states of Eastern Europe, the South Caucasus, or Central Asia,

– Both sides agree to limit the size of their military exercises,

– Neither the USA nor Russia will operate heavy bombers or surface warship in areas from which they can attack the other party,

– Neither the USA nor Russia will deploy nuclear weapons outside their own territory, and

– Neither will conduct nuclear weapons training of personnel from non-nuclear countries.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, Treaty between The United States of America and the Russian Federation on Security Guarantees (Moscow: 17 Dec 2021).

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, Agreement on measures to ensure the security of The Russian Federation and member States of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (Moscow: 17 Dec 2021).

- “Russia’s draft agreements with NATO and the United States: Intended for rejection?” Brookings Institution, 21 Dec 2021.

14. Peace Agreements Database, Minsk I (Minsk Protocol), University of Edinburgh, 09 May 2014.

15. US/NATO war goals

- “Western allies ramp up rhetoric against Russia, want ‘defeat’ of Moscow,” Politico.eu, 20 May 2022.

- “The Utter Necessity of a Russian Defeat,” The Hill, 20 May 2022.

- “The War Won’t End Until Putin Loses,” The Atlantic, 23 May 2022.

16. Western dissent over Kyiv peace proposals

- “NATO says Ukraine to decide on peace deal with Russia — within limits,” Washington Post, 05 Apr 2022

- Paul Pillar, “The Coming Dissent Over Ukraine’s Peace Terms,” National Interest, 05 Apr 2022.

17. “Pentagon chief’s Russia remarks show shift in US’s declared aims in Ukraine,” Guardian, 25 Apr 2022.

18. Vladimir Putin, “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians,” (Moscow: The Kremlin, 12 Jul 2021)

19. Putin’s revision of Russia-Ukrain history

- “Fact-checking Putin’s claims that Ukraine and Russia are ‘one people’,” U.Rochester Newscenter, 03 Mar 2022.

- “Putin’s one-sided history of Ukraine’s relationship with Russia,” Politifact, 23 Feb 2022.

20. “Putin’s new Ukraine essay reveals imperial ambitions,” Atlantic Council Ukraine Alert, 15 Jul 2021.

21. Putin, “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians,” op cit.

22. “Analysis: Why Russia’s Crimea move fails legal test,” BBC, 07 Mar 2014.

23. “Putin Pledges To Protect All Ethnic Russians Anywhere. So, Where Are They?” RFE/RL, 10 Apr 2014.

24. “Contextualizing Putin’s ‘On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians’,” Ukrainian Research Institute, Harvard University, 2 Aug 2021.

25. Crimea background

- “Analysts: Black Sea port in Ukraine still key to Russia’s naval interests,” Stars & Stripes, 03 Mar 2014.

- “Why Did Russia Give Away Crimea Sixty Years Ago?” Wilson Center, 22 Mar 2014

26. “Ukraine extends lease for Russia’s Black Sea Fleet,” The Guardian, 21Apr 2010.

27. “Russia’s Black Sea fleet in Sevastopol beyond,” Diploweb – La Revue Geopolitique, 23 May 2010.

28. “Russian Military Official Shifts Rhetoric, Says Army Now Focusing On ‘Liberation’ Of Eastern Ukrainian Regions,” RFE/RL, 25 Mar 2022.

29. Russia’s Military Interventions (Santa Monica CA: RAND. 2021)

30. Alexander Thalis, “Threat or Threatened? Russian Foreign Policy in the Era of NATO Expansion,” Australian Institute of International Affairs, 03 May 2018.

31. On “preventative war”

- “Iraq War lesson. ‘preventative wars’ are illegal wars, period,” Responsible Statecraft, 18 Mar 2022.

- “Beating Them To the Prewar,” New York Times, 28 Sep 2002.

- Mary Ellen O’Connell, “The Myth of Preemptive Self-Defense,” American Society of International Law, Aug 2002.

32. Russian nuclear use?

The probability of Moscow resorting to nuclear weapons remains very low because the likely consequences of such action is widely seen as catastrophic for all sides. However, the character of the war as an increasingly Russia-NATO proxy conflict and its proximity to Moscow increases the likelihood of desperate action should Russian failure loom. This is a conflict that Putin cannot afford to lose strategically or politically. So, should Russia face a categorical defeat in the field, the likelihood of intentional nuclear use will rise – and probably to a degree greater than that during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis. Even in this case it will remain low, although higher readiness levels and signalling on both sides will increase the likelihood of accidental use.

- “Putin could use nuclear weapon if he felt war being lost – US intelligence chief,” Guardian, 10 May 2022.

- “Russia Insists It Won’t Use Nuclear Weapons in Ukraine,” Newsweek, 19 Apr 2022.

- “CIA Chief Says Threat Russia Could Use Nuclear Weapons Is Something US Cannot ‘Take Lightly’,” RFE/RL, 15 Apr 2022.

- Lawrence Korb, “Why the War in Ukraine Poses a Greater Nuclear Risk than the Cuban Missile Crisis,” Just Security, 12 Apr 2022.

- “‘Battlefield nukes’ in Ukraine? A low but complex threat,” CSM, 11 Apr 2022.

- “Would Russia Use a Tactical Nuclear Weapon in Ukraine?” Modern War Institute, 16 Mar 2022.

- “Putin Orders Russian Nuclear Weapons on Higher Alert,” Arms Control Association, Mar 2022)

33. “The Soviet Union could not right the nuclear imbalance by deploying new ICBMs on its own soil. In order to meet the threat it faced in 1962, 1963, and 1964, it had very few options. Moving existing nuclear weapons to locations from which they could reach American targets was one.” Graham Allison and Philip Zelikow, Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis (New York: Addison Wesley Longman, 1999), pp. 94–95.

At the time, the USA had 203 ICBMs able to reach anywhere in the Soviet Union. The Soviets by contrast had 36 ICBMs able to hit anywhere in the USA. The planned Cuban deployment when finished would have comprised more than 80 intermediate- and medium-range missiles sitting just 90-miles off the US coast and thus able to function as proxy ICBMs. Also available would have been 90 shorter range nuclear missiles for defense of the island.

- “Last Nuclear Weapons Left Cuba in December 1962,” National Security Archive, 11 Dec 2013.

- “The Cuban Missile Crisis: A nuclear order of battle.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (20 Oct 2012)

- “What Was at Stake in 1962?” Foreign Policy (10 Jul 2012).

34. “The Geopolitics of Empathy,” Foreign Policy (27 Jun 2021).

35. Why Moscow fears NATO

- “The sources of Russia’s fear of NATO,” Communist and Post-Communist Studies (Apr 2018)

- Assessing Russian Reactions to US and NATO Posture Enhancements (Santa Monica CA: RAND 2017)

36. US practice of regime-change

- Template Revolutions: Marketing US Regime Change in Eastern Europe, Westminister Papers, 2017

- “American Covert Regime Change Operations: From the Cold War to the War on Terror,” Journal of International Affairs (23 Jul 2018)

- “The USA tried to change other countries’ governments 72 times during the Cold,” Washington Post. 23 Dec 2016.

- “Mapped: The 7 Governments the USA Has Overthrown,” Foreign Policy (20 Aug 2013)

- “Regime Change Doesn’t Work,” Boston Review (26 Jun 2012).

37. see ft. 31.

38. Moscow’s complaints about NATO expansion

- “Ukraine war follows decades of warnings that NATO expansion into Eastern Europe could provoke Russia,” The Conversation (28 Feb 2022).

- Peter Beinart, “Biden’s CIA Director Doesn’t Believe Biden’s Story about Ukraine,” peterbeinart.substack.com (07 Feb 2022).

- “NATO Expansion – The Budapest Blow Up 1994,” National Security Archive, 24 Nov 2021.

39. NATO Expansion: “What Gorbachev Heard,” National Security Archive, 12 Dec 2017.

40. Full text available in PISM, Documents Talk: NATO-RUSSIA Relations after the Cold War, The Polish Institute of International Affairs, 08 Dec 2020.

Also see: “Putin warns NATO over expansion,” Guardian, 04 Apr 2008.

41. “Transcript: Putin Speech and the Following Discussion at the 2007 Munich Conference on Security Policy,” Johnson’s Russia List, 27 Mar 2014.

42. Congressional Research Service, “The Cost of Iraq, Afghanistan, and Other Global War on Terror Operations Since 9/11″ (Washington DC: CRS, 08 Dec 2014)

43. US-Russia contention over Ukraine

- Short critical assessment of US efforts before and leading up to the original 2004 Ukrainian “Orange Revolution”: “US campaign behind the turmoil in Kiev,” Guardian, 25 Nov 2004.

- Critical assessment of recent Russian efforts to shape political developments in Ukraine: “The logic of competitive influence-seeking: Russia, Ukraine, and the conflict in Donbas,” Post-Soviet Affairs Vol. 34, No.4 (2018)

44. “Yanukovych set to become president as observers say Ukraine election was fair,” Guardian, 08 Feb 2010.

45. EU 2014 peace deal discarded

- “Ukraine Has Deal, but Both Russia and Protesters Appear Wary,” NYT, 22 Feb 2014.

- “Ukraine opposition signs crisis deal, but streets resist,” NY Post, 21 Feb 2014.

- “Agreement on the Settlement of Crisis in Ukraine – full text,” Guardian, 21 Feb 2014.

46 “Ukraine passes language law, irritating president-elect and Russia, Reuters, 25 Apr 2019.

47. “In Ukraine, nationalists gain influence – and scrutiny, Reuters, 07 Mar 2014.

48. Crimea voting trends and popular opinion

- “Percentage of Ukraine’s Population (by region) that voted for Tymoshenko or Yanukovych in the 2010 Presidential Election,” Central Election Commission Ukraine, Brookings Institution, 21 May 2015.

- “Despite Concerns about Governance, Ukrainians Want to Remain One Country,” Pew Research Center, 08 May 2014.

49. US officials supporting Maidan protestors

- “Russia cries foul over Western embrace of Ukraine’s demonstrators,” CSM, 13 Dec 2013.

- “Top US official visits protesters in Kiev as Obama administration ups pressure on Ukraine president Yanukovich,” CBS News, 11 Dec 2013.

50. “Ukraine crisis: Transcript of leaked Nuland-Pyatt call,” BBC, 07 Feb 2014.

51. UN General Assembly, Declaration on the Inadmissibility of Intervention and Interference in the Internal Affairs of States, 09 Dec 1981.

52. Separatist sentiment in Ukraine’s east

- “The Origins of Separatism: Popular Grievances in Donetsk and Luhansk,” Ponars Eurasia, 15 Oct 2015.

- “In Ukraine, nationalists gain influence – and scrutiny,” Reuters, 07 Mar 2014.

- “Percentage of Ukraine’s Population (by region) that voted for Tymoshenko or Yanukovych in the 2010 Presidential Election,” Central Election Commission Ukraine, Brookings Institution, 21 May 2015.

53. Donbas anti-Maidan rebels

- “A new, pro-Russia ‘Maidan’ in Ukraine’s east?” CSM, 08 Apr 2014.

- “Pro-Russian Protesters in Eastern Ukraine Seize Weapons,” VOA, 06 Apr 2014.

- “Pro-Russia protesters occupy regional government in Ukraine’s Donetsk,” Reuters, 03 Mar 2014.

54. Kyiv takes military action against Donbas rebels

- “Ukraine says Donetsk ‘anti-terror operation’ under way,” BBC, 16 Apr 2014.

- “Kiev government to deploy troops in Ukraine’s east,” AP, 13 Apr 2014.

55. Russian 2014 intervention

- “Ukrainian army closes in on Donetsk as rebel fighters call on Russia for help,” Guardian, 03 Aug 2014.

- “Ukraine Reports Russian Invasion on a New Front,” NYT, 28 Aug 2014.

56. “Security Service of Ukraine: Today 6,000 Russian military personnel and 40,000 militants fight in Donbas,” Ukraine Media Crisis Center, 15 Mar 2015.

57. Death toll during Ukraine civil conflict

- “Death Toll in Ukraine Conflict Hits 9,160, UN Says,” NYT, 03 Mar 2016.

- “US says about 500 Russian soldiers killed in eastern Ukraine,” Anadolu Agency News Broadcasting System (Turkey), 10 Mar 2015.

58. Minsk II agreement

- “Factbox: Minsk agreement on Ukraine,” Reuters, 12 Feb 2015.

- “Package of measures for the Implementation of the Minsk agreements,” UN Peacemaker, 19 Feb 2015.

59. “Ukraine unlikely to advance Minsk II despite talks,” Economist Intelligence Unit, 11 Jan 2022.

60. Far-right deadly revolt against Minsk agreement

- “Death Toll Rises To Three From Grenade Attack Near Ukrainian Parliament,” RFE/RL, 01 Sep 2015.

- “Far-Right Riot at Ukraine’s Parliament,” Institute for the Study of War, 01 Sep 2015.

61. “Ukraine parliament offers special status for rebel east, Russia criticizes,” Reuters, 17 Mar 2015.

Note: The 2015 special status law was provisional and, contrary to the Minsk agreement, it was not to come into effect until Donetsk and Luhansk held elections under Ukrainian law.

62. Outsize influence of Ukrainian extreme nationalists

- “Nationalist Radicalization Trends in Post-Euromaidan Ukraine,” Ponars Eurasia, May 2018.

- “Commentary: Ukraine’s neo-Nazi problem,” Reuters, 19 Mar 2018.

- “In Ukraine, Ultra-nationalist Militia Strikes Fear In Some Quarters,” RFE/RL, 30 Jan 2018.

63. Blockade of rebel areas

- “Cut Off: What Does the Economic Blockade of the Separatist Territories Mean for Ukraine?” Focus Ukraine, Wilson Center, 9 Jan 2018.

- “Ukraine orders blockade on rebel-held east,” Deutsche Welle, 15 Mar 2017.

- “In Ukraine, blockade threatens to force issue at heart of civil war,” CSM, 28 Feb 2017.

- “Donbas Blockade Exposes Political Fault Lines in Ukraine, Eurasia Daily Monitor 14:24 (24 Feb 2017).

64. Donbas Reintegration Law

- “Ukraine Moves To Restore Control Over Separatist-Held Areas, “ RFE/RL, 18 Jan 2018.

- “Donbas Reintegration Law: What Impact on the Minsk Agreements?” Strike, 09 Mar 2018.

65. Kyiv’s new military policy on Donbas

- “Ukraine’s New Military Engagement in the Donbas,” Strategic Europe, Carnegie Europe, 03 May 2018.

- “Ukraine Declares ‘Anti-Terrorist Operation in the Donbas’ Officially Over: What Does That Mean?” RUSI, 16 May 2018.

- “Old war, new rules: what comes next as ATO ends and a new operation starts in Donbas?” Ukraine Crisis Media Center, 04 May 2018.

- “What Does Ukraine’s New Military Approach Toward the Donbas Mean?” Atlantic Council, 15 May 2018.

66. Ukraine seeks to revise Minsk agreement and process

- “President of Ukraine calls for revamp of peace process to end Donbas war,” President of Ukraine Official Website, 26 April 2021.

- “Zelensky offers to involve U.S., UK, Canada in Normandy talks,” UNIAN (Ukrainian Independent Information Agency), 26 Apr 2021.

67. NATO Security Assistance to Ukraine: Arms and Training

- Congressional Research Service, US Security Assistance to Ukraine (Washington DC: CRS, 29 Apr 2022)

- “Lethal Weapons to Ukraine: A Primer,” Atlantic Council, 26 Jan 2018.

- “The Secret of Ukraine’s Military Success: Years of NATO Training,” WSJ, 3 Apr 2022.

- “As the Russian threat grew, US intelligence ties to Ukraine deepened,” Yahoo News, 02 Feb 2022.

- “CIA-trained Ukrainian paramilitaries may take central role if Russia invades,” Yahoo News, 13 Jan 2022.

- “Mission Ukraine: US Army Leads Multinational Training Group to Counter Russian Threat,” Association of the United States Army, 19 May 2020.

- “Ukrainian Special Forces Getting Western Help, Training,” SOFREP, 08 Mar 2019.

- “In Ukraine, the US Trains an Army in the West to Fight in the East,” Defense One, 05 Oct 2017.

- “US, allies give Ukrainians a boost in building modern army,” Stars & Stripes, 06 Jul 2017.

- “The USA and Ukraine have started military training exercises despite Russian objections,” Insider, 20 Apr 2015.

68. Joint Exercises

- “Ukraine holds military drills with US forces, NATO allies,” Reuters, 20 Sep 2021.

- “The US-Ukraine Sea Breeze naval exercises, explained,” Washington Post, 02 Jul 2021.

- “Military from 5 NATO states to take part in Ukrainian-British drills,” Kyiv Post, 04 Apr 2021.

- “US Air Force’s huge exercise in Ukraine fuels growing partnership and that country’s NATO ambitions,” Air Force Times, 13 Nov 2018.

- “Ukraine-NATO Joint Military Exercises Begin In Lviv Region,” RFE/RL, 03 Sep 2018.

- “US and NATO troops begin Ukraine military exercise,” BBC, 15 Sep 2014.

69. “Ukraine Votes To Abandon Neutrality, Set Sights On NATO,” RFE/RL, 23 Dec 2014.

70. “Ukraine President Signs Constitutional Amendment On NATO, EU Membership,” RFE/RL, 19 feb 2022.

71. “NATO officially gives Ukraine aspiring member status; membership action plan is next ambition,” Euromaidan Press, 10 Mar 2018.

72. “NATO recognises Ukraine as Enhanced Opportunities Partner,” NATO News, 12 Jun 2020.

73. US rejects Russian security proposals

- “US refuses to budge on Ukraine in response to Russian demands,” LA Times, 26 Jan 2022.

- “Putin accuses US, allies of ignoring Russian security needs,” AP, 1 Feb 2022.

74. “The Indivisibility of Euro-Atlantic Security,” presentation by OSCE Secretary General Marc Perrin de Brichambaut, 18th Partnership for Peace Research Seminar, Vienna Diplomatic Academy, 4 Feb 2010.

75. Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, “Charter for European Security,” Istanbul Document 1999 (Vienna, Austria: OSCE, 1999)

76. NATO, Study on NATO Enlargement (Brussels: NATO, 03 Sep 1995)

77. NATO’s “Open Door”

- “Article X is conditional. New members can join NATO only if their membership would enhance regional security.” Michael O’Hanlon and Stephen Van Evera, “There is no NATO open-door policy,” The Hill, 27 Jan 2022.

- Amb. James Dobbins, “Should NATO Close Its Doors?” RAND Blog, 02 Feb 2022.

- Daniel DePetris, “NATO should shut the door, but not because Russia said so,” Defense News, 19 Jan 2022.

78. NATO, The North Atlantic Treaty (Brussels, 4 Apr 1949)

79. See Article 2(1). United Nations Charter (New York: UN, 26 Jun 1945)