Confounding current policy on the new Syria is the 2018 designation of the nation’s new leading organization, Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS, Levant Liberation Committee) as a terrorist group. This carries forward from the earlier assessment of a precursor organization, Jabhat al-Nusra, that was a local affiliate of Al Qaeda. (The US State Department had designated the Al-Nusra Front a “foreign terrorist” in 2012.)

Confounding current policy on the new Syria is the 2018 designation of the nation’s new leading organization, Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS, Levant Liberation Committee) as a terrorist group. This carries forward from the earlier assessment of a precursor organization, Jabhat al-Nusra, that was a local affiliate of Al Qaeda. (The US State Department had designated the Al-Nusra Front a “foreign terrorist” in 2012.)

Whatever else may be said of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, its recent practice belies the terrorist label. (See addendum on why terrorism designations are sometimes problematic.) Especially relevant in this case, HTS has disavowed extra-territorial violence. At present, the most critical international security concern regarding Syria is its stabilization – and that requires immediate and substantial aid and sanction relief. It also hinges on the new government’s capacity to restore sovereignty. Should the new government reverse course and pose a threat to global peace, the international community can adjust policy accordingly. But first things first.

Two outstanding challenges to sovereignty and legitimacy are the presence of foreign troops and the status of Kurdish areas. These two intertwine insofar as Turkish troops target the Kurdish areas while US troops defend them. It’s certain that Syria’s Kurdish minority will not simply return to the status quo antebellum. Also infeasible is ongoing Kurdish control of one-third of Syria’s land area and 70% of its oil wealth, given that Kurds constitute only 10% of the country’s population.

Finding and underwriting a stable balance among the security concerns of Damascus, Turkey, and Syria’s Kurdish community is key to the country’s stability as well as the stability of contiguous states. The essential formula would be a secure Turkey-Syria border and a real guaranteed degree of local autonomy for Kurdish areas within a unitary Syrian state. But Washington must resist any temptation to establish a “protectorate” – a client Kurdish proto-state dependent on a persisting US military presence. This would not be a recipe for peace, but rather the opening chapter of renewed internationalized civil war.

Background

More than simply a civil conflict, the Syrian war has had from the start a regional and global character. Foreign states and non-state actors intervened pursuing conflicting agendas. The interlopers included Russia, Iran, Turkey, Lebanon, Libya, the United States, the UK, France, and several Gulf States as well as Al Qaeda, ISIL, and other Iraqi, Iranian, Lebanese, Uzbek, and Chechen Islamist militias. These fed money, munitions, and/or fighters into the conflict contributing to its intractable character and appalling death toll. This did not serve the Syrian people or the region well.

As for the “best laid plans” of the foreign interlopers – few would have expected or chosen HTS to win state power. But it has. That speaks to the chaotic character of a multi-variate conflict. Like the Iraq and Libyan wars before it, the best laid plans of interventionists went terribly awry.

Syria’s New Reality

Today, the defacto governing authority of Syria, the transitional government, is led and essentially controlled by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) – a militant Islamist organization incorporating among its constituent parts some strains of jihadism and salafism and with leading elements that were an Al Qaeda associated movement (AQAM) eight years ago. That said, with its leaders having disavowed association with Al Qaeda in 2016, its more recent past and popular success are due to moderation, pragmatism, professionalism, and social service. Ruling a disparate population effectively and efficiently has required some liberalization. Still, their practice in governing Idlib was not been democratic. “Consultative authoritarianism” may best describe it, although their application of Sharia law has not been totalitarian.

Today, the defacto governing authority of Syria, the transitional government, is led and essentially controlled by Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) – a militant Islamist organization incorporating among its constituent parts some strains of jihadism and salafism and with leading elements that were an Al Qaeda associated movement (AQAM) eight years ago. That said, with its leaders having disavowed association with Al Qaeda in 2016, its more recent past and popular success are due to moderation, pragmatism, professionalism, and social service. Ruling a disparate population effectively and efficiently has required some liberalization. Still, their practice in governing Idlib was not been democratic. “Consultative authoritarianism” may best describe it, although their application of Sharia law has not been totalitarian.

HST’s record on respect for human rights as defined by the UN’s Universal Declaration falls short. It certainly gives reason for concern – although HTS’ practice since 2016 is much better than that of its principal precursor, the Al-Nusra Front, and incomparably better than the Islamic State or the Assad regime. Examining 505 reported incidents of unlawful killing by HTS and its precursor since 2012, the Syrian Network for Human Rights found that 67% occurred during the period 2012-2015 while 8.5 percent occurred during 2020-2021, which on a yearly basis implies a four-fold improvement. (Of course, this sample may not accurately reflect the distribution of such events.)

More recently, the UN human rights investigation unit that visited Syria in December 2024 after the transition reported “encouraging signs by new authorities to engage on human rights issues.” Looking forward, efforts by the new government to extend its writ beyond the areas it currently controls could easily involve an uptick in repressive measures. (As of January 1, 2025, it seems the transitional government exercises reliable control over areas containing more than 70% of the population.) However, videos are already circulating online purportedly showing HTS allies attacking refugee Syrian Alawites in Lebanon. Their origin and authenticity are not clear, but concern is due.

While substantial, these concerns do not warrant a “probationary period” before lifting sanctions and lending relief, however. Such would unnecessarily add to the difficulties facing the new government, weakening its writ and possibly giving more radical elements sway. Most important, a “wait and see” approach fails to appreciate that instability and centrifugal tendencies pose the most real and greatest danger at present.

Recognizing and assisting the new provisional government in stabilizing Syria also should not depend on whether the government adheres to any external model of social and economic organization – Islamic, Socialist, or Democratic. It is past time for crusading nations to set aside discredited visions of regime change and coercive nation building. The Syrian war, like the Iraq and Afghan wars before it, shows such efforts to be not only exorbitant but, on balance, ineffective and subject to quagmire and blowback. Major global and regional powers should eschew attempts to leverage Syria’s current dire circumstance in hope of “shaping” the new government in ways that conform to exclusive foreign interests.

The question on which recognition should most hinge is whether, absent outside intervention, the new government can likely achieve sovereign authority in the country and do so without the type of gross human rights abuses or cross-border militancy that poses a threat to regional or global peace. Looking forward, any near term assessment of these qualities is obviously probabilistic. But uncertainty in this regard must be weighed against the real and present danger of instability that could re-ignite war.

Given the urgency of stabilizing the country, the new provisional government provisionally meets the criteria for assistance, which should be immediately forthcoming. As noted in the introduction, should the new Syrian government reverse course and pose a threat to regional and global peace, the international community can adjust policy accordingly.

Issues related to re-establishing Syrian sovereignty

The presence of foreign troops on Syrian soil directly violates the nation’s sovereignty, excepting those invited by national authorities and operating under the equivalent of a Status of Forces Agreement. Today, there are significant contingents of foreign forces operating inside Syria (not including the occupied Golan Heights): 8,000- 10,000 Turkish troops, 2,000+ US troops, and 4,000-5,000 Israeli troops. Of these, only the Turkish contingent is likely acceptable to the new government, although even in this case the new government’s control over the contingent is probably limited. Turkey also exercises controlling influence over one portion of the Syrian rebel coalition – arguably the largest: the Syrian National Army, comprising a multitude of factions.

The presence of foreign troops on Syrian soil directly violates the nation’s sovereignty, excepting those invited by national authorities and operating under the equivalent of a Status of Forces Agreement. Today, there are significant contingents of foreign forces operating inside Syria (not including the occupied Golan Heights): 8,000- 10,000 Turkish troops, 2,000+ US troops, and 4,000-5,000 Israeli troops. Of these, only the Turkish contingent is likely acceptable to the new government, although even in this case the new government’s control over the contingent is probably limited. Turkey also exercises controlling influence over one portion of the Syrian rebel coalition – arguably the largest: the Syrian National Army, comprising a multitude of factions.

Affirming Syrian sovereignty entails expeditiously withdrawing all foreign forces not explicitly invited by the new government. Among the reasons that both Turkey and Israel would resist exiting is their concern about active cross-border threats. (The case of the US intervention forces is addressed below.) Although Israeli and Turkish concerns don’t justify seizing Syrian territory to serve as buffer zones, there are ways to address these concerns if Damascus agrees – as it has done before. Neutral “imposition forces” could occupy and patrol those buffer zones that have already or recently been defined along the Golan Heights and the Turkey-Syria border. However, in both cases, future imposition forces should operate under UN mandate and control.

Affirming Syrian sovereignty entails expeditiously withdrawing all foreign forces not explicitly invited by the new government. Among the reasons that both Turkey and Israel would resist exiting is their concern about active cross-border threats. (The case of the US intervention forces is addressed below.) Although Israeli and Turkish concerns don’t justify seizing Syrian territory to serve as buffer zones, there are ways to address these concerns if Damascus agrees – as it has done before. Neutral “imposition forces” could occupy and patrol those buffer zones that have already or recently been defined along the Golan Heights and the Turkey-Syria border. However, in both cases, future imposition forces should operate under UN mandate and control.

Although a northern buffer zone was once briefly sufficient to address Turkish President Erdogan’s concern about cross-border Kurdish activity, he has more recently been intent on deploying the Turkish military to destroy the Kurdish Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) altogether. How the new Syrian government integrates AANES and its armed forces may alter Turkey’s stance. Also, both the United States and the European Union could employ positive inducements to moderate Erogan’s position. Substantial material support for robust UN imposition forces would certainly help insulate Turkey from cross-border threats (while insulating the Kurd’s from Turkish assaults).

The future of Syria’s Kurdish community

The disposition of Syria’s Kurdish region poses other challenges apart from Turkey-AANES relations. Negotiating a practicable plan for reintegration is key to both stability and to the central government’s legitimacy. But what degree of autonomy will the Kurdish region enjoy? Damascus will certainly resist the region conducting independent foreign relations. The disposition of oil resources is another point of possible contention. Seventy percent of Syria’s oil resources are in the Kurdish-controlled area. Damascus will certainly require that control of these resources – which remain largely untapped by the Kurds – return to national authorities. This, the Kurdish authorities have said they are willing to do, provided a fair distribution of il resources among Syria’s provinces.

Also at issue: What will be the future disposition of the Kurdish armed forces, which are mostly mobile and mechanized infantry? Clearly, Syria cannot go forward hosting two independent mechanized armed forces. It would be a challenge to the nation’s sovereignty. However, until the Turkey-Syria border is secured and the status of the Kurdish area agreed, the maintenance of the Kurdish armed forces can serve for the Kurds as a confidence and security-building measure – provided that central government officers are added as observers to leading bodies. A transitional period of 2-4 years seems reasonable given present levels of threat (from the Islamic State and Turkey) and distrust.

Also at issue: What will be the future disposition of the Kurdish armed forces, which are mostly mobile and mechanized infantry? Clearly, Syria cannot go forward hosting two independent mechanized armed forces. It would be a challenge to the nation’s sovereignty. However, until the Turkey-Syria border is secured and the status of the Kurdish area agreed, the maintenance of the Kurdish armed forces can serve for the Kurds as a confidence and security-building measure – provided that central government officers are added as observers to leading bodies. A transitional period of 2-4 years seems reasonable given present levels of threat (from the Islamic State and Turkey) and distrust.

Eventually, heavier Kurdish mechanized and artillery units should be integrated into Syrian national armed forces, although the unique Kurdish identity of the units could be maintained – a not uncommon practice. Lighter paramilitary units might remain in association with future Kurdish provincial authorities.

Managing the Islamic State Remnants

Activity by remnants of the Islamic State in Syria is much reduced today, reflecting a cadre base that is disbursed and only 5-6% of its previous peak strength. It remains a serious concern but, going forward, the task of managing and combating ISIL on Syrian soil should be the province of the central Syrian government, acting together with Kurdish and foreign partners as Damascus sees fit.

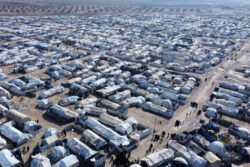

Another urgent matter is the ongoing long-term internment of ~40,000+ people suspected of Islamic State membership, or of a family relationship to suspected members, or simply suffering displacement due to anti-IS operations. (Only 10% of those held are thought to be ISIL cadre, and only a subset of these are thought to have been fighters.) This mass incarceration lacking due process is an egregious violation of human rights and international law and must be urgently rectified. The responsibility for processing Syrian ISIL-rleated individuals should fall to Damascus. Foreign nationals might be processed through an international tribunal. The prospect of visa sanctions may encourage other origin countries to accept the return of their nationals. There is an urgent need for international material support to resolve the status of these internees, ASAP.

Another urgent matter is the ongoing long-term internment of ~40,000+ people suspected of Islamic State membership, or of a family relationship to suspected members, or simply suffering displacement due to anti-IS operations. (Only 10% of those held are thought to be ISIL cadre, and only a subset of these are thought to have been fighters.) This mass incarceration lacking due process is an egregious violation of human rights and international law and must be urgently rectified. The responsibility for processing Syrian ISIL-rleated individuals should fall to Damascus. Foreign nationals might be processed through an international tribunal. The prospect of visa sanctions may encourage other origin countries to accept the return of their nationals. There is an urgent need for international material support to resolve the status of these internees, ASAP.

Relevant to efforts to reform ISIL members is the distinction between the Islamic State and Bin Laden’s core al-Qaeda. Unlike Bin Laden’s cabal, the Islamic State in Syria was not a small tightly-knit insular group. It has more resembled an indigenously-rooted mass insurgency organization whose extremism grew in reaction to a specific local circumstance: the occupation of Iraq by western forces, the rise to dominance of the Iraqi Shiite community, and the prison camps established by the Coalition Authority. This localism is true regardless of the international spread of its brand. Under new circumstances, a significant number of ISIL members and fellow travelers might be peeled away from the group’s communal violence, its takfir ideology, and integrated in Syria’s new Islamic polity. Already Arab tribes are playing a role in managing the internment and reintegration of ISIL members, although the process is too slow and under-supported.

The threat that ISIL affiliates and aspirants pose to the United States and the broader international community have been and are most effectively addressed locally through measure of homeland security and law enforcement. Securing the US homeland does not require the ongoing deployment of US troops in Syria; Indeed, such deployments can motivate attacks on the United States. Of course, the option of directly interdicting cross-border assaults from over the horizon is always available.

Addendum: The critical distinction between extremist cabals and mass insurgency organizations and movements

The definition and designation of “terrorist” entities (states, groups, or individuals) is problematic. Security policy would benefit by distinguishing between groups like bin-Laden’s Al Qaeda and indigenous insurgencies. Unfortunately, counter-terrorism rubrics usually do not. There’s a meaningful distinction between these two types of organization even when indigenous insurgencies seek to borrow on the militant Al Qaeda brand.

Al Qaeda (ALQ) was a rootless clandestine group famed for mass casualty attacks on soft and civilian targets as a form of messaging. Its objective was to catalyze global jihad through such acts in some diffuse way. Core ALQ’s practice did not depend on mass mobilization, nor was it in any way rooted among specific indigenous communities and their struggles. Even in Pakistan and Afghanistan, Al Qaeda was an interloper. Its violence – including mass casualty attacks – is unbounded in time, place, and scope. And that constitutes its unique threat.

By contrast, a national insurgent organization must be rooted among a population, drawing on it and mobilizing it, if it is to survive, prosper, and lead. Its viability and rise to power depends on devising and enacting a practical program of mass mobilization and governance. Otherwise such organizations wither and sink into obscurity. These are limiting condition that help set it apart from itinerant extremist organizations. And the difference is evident in the evolution of HTS from an Al Qaeda affiliate in 2012 to its present form.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Debate over Terrorist Designation

- BBC, Syria’s rebel leaders say they’ve broken with their jihadist past – can they be trusted? 19 Dec 2024

- Washington Institute, How Hayat Tahrir al-Sham Landed on U.S. Terrorist Lists – and Why It Should Stay There for Now, 17 Dec 2024

- Reuters, Could UN sanctions on Syrian rebels HTS be removed? 13 Dec 2024

- Long War Journal, Hayat Tahrir al Sham’s terror network in Syria, 12 Dec 2024

- Politico, US debates lifting terror designation for main Syrian rebel group, 09 Dec 2024

- Politico, Do Syria’s liberators still deserve the terrorist label? 09 Dec 2024

- Middle East Monitor, UK may remove HTS from terror list amid ‘fluid’ situation in Syria, 09 Dec 2024

- UN News, The de facto authority in Syria is a designated terrorist group: What happens now? Dec 2024

- CSIS, Examining Extremism: Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS), 03 August 2023

- Washington Institute, The Age of Political Jihadism: A Study of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, 09 May 2022

- Syrian Network for Human Rights, The Most Notable Hay’at Tahrir al Sham Violations Since the Establishment of Jabhat al Nusra to Date, 31 Jan 2022

On the Syrian Transitional Government

- Reuters, Syria appoints some foreign Islamist fighters to its military, sources say, 31 Dec 2024

- Axios, USA raises concerns about attacks on minorities with new Syrian government, 30 Dec 2024

- Reuters, Syrian ex-rebel factions agree to merge under defence ministry, 24 Dec 2024

- Arab Center DC, Rebuilding and Strengthening Syria’s State Institutions, 23 Dec 2024

- VOA News, Syria’s new rulers appoint defense, foreign ministers, 21 Dec 2024

- NPR, Who’s been funding the HTS rebels now in control of Syria? Updated, 20 Dec 2024

- Crisis Group, UN Security Council Is Finding Rare Consensus on Syria — For Now, 19 Dec 2024

- The Cradle, Syria’s de facto ruler says foreign extremists ‘deserve Syrian citizenship’, 17 Dec 2024

- Al Jazeera, What to know about Syria’s new caretaker government, 15 Dec 2024

- Chatam House, While international support is crucial, Syrians must lead their country’s political transition, 11 Dec 2024

- US Naval Institute Staff, Report to Congress on Syrian Regime Change, 10 Dec 2024

- Semafor, The cost of Syria’s reconstruction is slowly coming into focus, 10 Dec 2024

- Counterpunch, Understanding the Rebellion in Syria, 10 Dec 2024

- Al Monitor, Syria’s new foreign, defense ministers close to Turkey, influential in HTS, Dec 2024

- Washington Institute, The Age of Political Jihadism: A Study of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, 09 May 2022

- BBC, Syria war: Who benefits from its oil production? 20 Nov 2019

Human Rights Issues

- OHCHR, UN Commission of Inquiry team visits Syria, welcomes encouraging signs by new authorities to engage on human rights issues, and urges protection of mass graves and evidence, 20 Dec 2024

- Human Rights Watch, Syria: Civilians at Risk Amid Renewed Hostilities, 4 Dec 2024

- OHCHR, Rampant human rights violations and war crimes as war-torn Idlib faces the pandemic, 07 July 2020

- Amnesty International, Syria: ‘Nowhere is safe for us’: Unlawful attacks and mass displacement in north-west Syria, 10 May 2020

- Amnesty International, ‘We Leave or We Die’ ‘We Leave or We Die’ – forced Displacement under Syria’s ‘Reconciliation’ Agreements, 13 Nov 2017

US Policy re:New Syria

- Defense Priorities, What to Do? Wait and see: A post-Assad Syria, 23 Dec 2024

- Long War Journal, US removes $10 million reward for Hayat Tahrir al Sham leader, 22 Dec 2024

- Military.com, It’s Time for US Troops to Leave Syria, 20 Dec 2024

- Wash Post, US lifts bounty on Syria’s interim leader amid diplomatic outreach, 20 Dec 2024

- BBC, US scraps $10m bounty for arrest of Syria’s new leader Sharaa, 20 Dec 20924

- Defense One, Assad’s fall lays the ground for wider peace – if the US can seize the moment, 20 Dec 2024

- Lawfare, Our Man in Damascus? Sanctions and Governance in Post-Assad Syria, 13 Dec 2024

- CRS, Syria: Regime Change, Transition, and US Policy, 13 Dec 2024

- Aaron Mate, In Syria dirty war, “our side” has won, 12 Dec 2024

- Long War Journal, US launches massive strikes on Islamic State as Hayat Tahrir al-Sham deposes Assad regime, 09 Dec 2024

- Middle East Eye, US repeats Israel’s ‘right to defend itself’ after seizure of buffer zone with Syria, 9 Dec 2024

- Reuters, Foreign armies in Syria and how they came to be there, 06 Dec 2024

- FDD, America Must Stand with Syria’s Kurds, 4 Dec 2024

- TWZ, Claims Swirl Around US Strikes In Eastern Syria (Updated). 3 Dec 2024

2016 Controversy Over targeting Al-Nusra Front

- BBC, US protecting Syria jihadist group – Russia’s Lavrov, 30 Sept 2016

- US State Dept, Remarks With Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and UN Special Envoy Staffan de Mistura at a Press Availability, 9 Sept 2016

Syrian Kurdish Community

- WOTR, Does the Fall of Assad Re-Open Turkey’s Kurdish Pandora’s Box? 23 Dec 2024

- Arab Center, Syria’s Kurds Facing Dangerous Headwinds, 18 Dec 2024

- RUDAW, US mediation efforts fail to secure truce with Turkey, says SDF, 16 Dec 2024

- VOA News, Syrian Kurds seek to preserve autonomy following Assad’s fall, 13 Dec 2024

- RUDAW, SDF says has deals with HTS, to send a delegation to Damascus, 12 Dec 2024

- The Cradle, US proxies in Syria ‘plea’ with Israel for help after HTS-led extremists attack ISIS prisons, 12 Dec 2024

- Carnegie Endowment, Eastern Syria After Assad; The SDF has expanded its control over Deir al-Zor, but may soon find itself overstretched and facing Turkish allies, 10 Dec 2024

- Arab Center, Syrian Kurds in an Increasingly Precarious Position, 18 Oct 2023

- OYRX, Kurdish Armour: Inventorying YPG Equipment In Northern Syria, Oct 2021

- Military Matters, Mobile and Armoured Forces of the Syrian Democratic Forces against ISIS, 27 Aug 2021

- FPIF, US Commission Calls for Recognition of Rojava, 14 May 2021

- Cambridge University Press, Approaches to Kurdish Autonomy in the Middle East, 23 Oct 2019

- CSIS, Settling Kurdish Self-Determination in Northeast Syria, 29 Jan 2019

- Crisis Group, Syria’s Kurds: A Struggle Within a Struggle, 22 Jan 2013

Islamic State in Syria (including its internment)

- Washington Institute, Syria Crisis Leaves Islamic State Prisons and Detention Camps Vulnerable, 09 Dec 2024

- Hudson Institute, Remaining, Waiting for Expansion (Again): The Islamic State’s Operations in Iraq and Syria, 05 Dec 2024

- Just Security, Assessing Amnesties and Re-assimilation in Northeast Syria, 7 Nov 2024

- USCENTCOM, Defeat ISIS Mission in Iraq and Syria for January-June 2024, 16 Jule 2024

- OHCHR Syria, The Lawfulness of Women’s Deprivation of Liberty in al-Hol Camp, May 2024

- Amnesty International, Syria: Mass death, torture and other violations against people detained in aftermath of Islamic State defeat, April 2024

- Guardian, US and UK complicit in detentions at Syrian camps where torture rife, 17 Apr 2024

- Washington Institute, One Year of the Islamic State Worldwide Activity Map, 20 Mar 2024

- Washington Institute, Five Years After the Caliphate, Too Much Remains the Same in Northeast Syria, 19 Mar 2024

- Just Security, A Tribunal for ISIS Fighters – A National Security and Human Rights Emergency, 30 Mar 2021

- International Security, Understanding the Islamic State – A Review Essay, Spring 2016

Post-Assad Israeli Operations on Syria

- Columbus Jewish News, IDF advances deep into Quneitra city in Syria, 30 Dec 2024

- Arab Center, Israel, Syria, and International Law, 26 Dec 2024

- ACLED, Syria: Israeli airstrikes reach an all-time high after Assad regime falls, 19 Dec 2024

- VOA News, New details emerge on Israel’s actions in Syrian buffer zone, change in US position, 18 Dec 2024

- All Israel, Israel expands operations in Syria, secures buffer zone against jihadi threats, 14 Dec 2024.

- IDF, The IDF Struck Strategic Weapons Stockpiles in Syria, 12 Dec 2024

- New Arab, Israeli PM Netanyahu says occupied Golan Heights Israeli ‘for eternity’, 09 Dec 2024

- Times of Israel, IDF deploys in Golan buffer zone with Syria, girding for post-Assad regime chaos, 08 Dec 2024,

Turkey’s Role in Syrian Rebellion & Afterrmath

- Middle East Eye, Syria will establish strategic relations with Turkey, says HTS leader, 18 Dec 2024

- The Cradle, Turkiye provides ‘air support’ to extremists violating ceasefire in north Syria: SDF, 18 Dec 2024

- YNET News, Turkey quick to establish facts on the ground in Syria, offers military training, 15 Dec 2024

- UKRINFORM, Turkey will help Syria to create 300,000 army, 12 Dec 2024

- Foreign Affairs.com, How Turkey Won the Syrian Civil War, 11 Dec 2024

- Stimson, What Turkey Hopes to Gain From the HTS Offensive in Syria, 05 December 2024

- Human Securty Centre, The Militarization and Exploitation of Northern Syria, 06 May 2024

- Asharq Al-Awsat, Türkiye Establishes Presence in Syria with 10,000 Soldiers, Dozens of Military Bases, 04 February 2023

Assessing and Managing the Foreign Terrorist Threat to the US Homeland

- GWU Program on Extremism, ISIS in America: From Retweets to Raqqa, December 2015

- Ohio State University Mershon Center and Cato Institute, Terrorism since 9/11: The American Cases, April 2015

- RAND, Would-Be Warriors Incidents of Jihadist Terrorist Radicalization in the United States Since September 11, 2001. 2010

- PDA, War & Consequences: Global Terrorism has Increased Since 9/11 Attacks, 25 Sept 2008

A Critical Distinction: Extremist Cabals versus Mass Insurgency Organzation

- The Cambridge History of Strategy, Terrorism and Insurgency, 06 jan 2025

- Terrorism and Political Violence Vol 26, 2024, Terrorism, Guerrilla, and the Labeling of Militant Groups, 08 Mar 2023

- Cato Institute, Conflating Terrorism and Insurgency, 28 Feb 2016

- Crime, Law, and Social Change, Terrorism versus insurgency: a conceptual analysis, 21 January 2016

- The Character of War in the 21st Century, Chap 2, Insurgency and terrorism Is there a difference? 2010