Carl Conetta, Project on Defense Alternatives, 14 Feb 2022

Summary: Moscow will act when and if it declares that the West has escalated contention rather than responding positively to its entreaties – principally those regarding NATO expansion and implementation of the Minsk II agreement. Recent, new US/NATO troop deployments and weapon transfers to Ukraine may already count as relevant escalation. Russian forces surrounding Ukraine stand at an exceptionally high level of readiness and significantly exceed the scale of previous deployments. Nonetheless, a full-scale invasion aiming to seize the whole of Ukraine is highly unlikely. Indeed, Russian action may involve no more than large-scale conveyance of weapons and munitions to the rebel areas, possibly along with an influx of “volunteers.” Several other options ranging between these two are discussed below.

Summary: Moscow will act when and if it declares that the West has escalated contention rather than responding positively to its entreaties – principally those regarding NATO expansion and implementation of the Minsk II agreement. Recent, new US/NATO troop deployments and weapon transfers to Ukraine may already count as relevant escalation. Russian forces surrounding Ukraine stand at an exceptionally high level of readiness and significantly exceed the scale of previous deployments. Nonetheless, a full-scale invasion aiming to seize the whole of Ukraine is highly unlikely. Indeed, Russian action may involve no more than large-scale conveyance of weapons and munitions to the rebel areas, possibly along with an influx of “volunteers.” Several other options ranging between these two are discussed below.

Given the forecasts, premonitions, and warnings emanating from Washington regarding a prospective Russian invasion of Ukraine, one would think it a foregone conclusion. And maybe, it is – even though seizing the country and subjugating its 44 million people would be an unparalleled nightmare for Moscow. And that’s true regardless of threatened sanctions. (By comparison, the 2014 seizure of Crimea was easy; It is small region (pop. 2.4 million) that had been positively inclined toward Russia and was already hosting thousands of Russian military personnel on the eve of annexation.)

Has Washington been hoping to deter a Russian invasion by forecasting it, threatening punishment, bolstering Ukraine’s weapon stocks, and redoubling the type of European military deployments about which Moscow incessantly complains? A curious feature of the recent NATO military preparations and enhancements is that, while sure to irritate Moscow, they fall far short of what might deter invasion. Perhaps these, like Washington’s warnings and prognostications, are meant mostly to rally NATO and burnish the image of American leadership. Another distinctive feature of US pronouncements is that they comprise mostly threats and little in the way of positive inducements. In some respects, America’s framing of the crisis cannot fail: If Russia invades, then America is proved insightful; If it does not invade, then America can claim effective deterrence. And yet, there are options for Moscow to spoil both expectations.

The road to current options

Weighing what Moscow might do now or soon requires a look back at the recent evolution of the crisis. Russia’s attempted intimidation of Ukraine by massing troops on its border has occurred frequently since Jan 2015, always linked to (i) Ukrainian action concerning the eastern rebels or Ukraine’s Russian-speaking citizens, (ii) Ukranian steps toward NATO, or (iii) weapon deliveries from the USA or NATO.

Since early 2020, Russian military pressure has been linked to the lack of progress toward fully implementing the Minsk II agreement, President Zelenskyy’s desire to revise provisions of the accord regarding autonomy for rebel areas, his pronounced campaigning for NATO membership, NATO’s June 2020 grant to Ukraine of “enhanced opportunities partner” status, the transfer of lethal weapons from NATO countries (beginning in 2017), and joint Ukraine-NATO training and exercises. From Moscow’s perspective, the likelihood of full Minsk II implementation is progressively diminishing, while Ukraine’s approach to NATO advances, and its capacity to retake the eastern rebel areas improves. This argues against patience, especially given the failure of western capitals to incentivize Ukrainian acceptance of key Minsk II provisions.

Upping the ante

In Dec 2021, Moscow seemed to broaden the scope of prospective negotiations by offering a draft “Treaty between The United States of America and the Russian Federation” regarding security guarantees. This document outlined rather ambitious proposals to mutually limit behavior that Moscow perceived as undermining the core security interests of the signatories, especially itself. These included ending the eastward expansion of NATO and, indeed, denying ascension to any former member state of the USSR (presumably meaning Georgia). The treaty would also forbid deployment of nuclear weapons outside national territory, and forbid the dispatch of heavy bombers, warships, or missiles to areas outside national territory from which they can attack the other’s home territory.

The document seems to be more a public enumeration of security complaints than a practical foundation for near-term negotiations. It’s too ambitious. However, while it does not mention the ongoing dispute regarding Ukraine’s civil conflict, it may have been meant to put that dispute into the context of Russia’s overall and long-standing security complaints. In this context, a western push to fully and soon implement the Minsk II agreement would seem a modest concession to Moscow’s concerns. Now, in the opinion of many western leaders and commentators, grants of autonomy for the rebel areas would also scuttle Ukraine’s hopes for NATO membership – as Moscow desires. But such an exclusion is speculative and proffered mostly as additional argumentation against granting the eastern rebel zones true autonomy. (A number of NATO members have nettlesome regions, population segments, political tendencies, or even state leaders.)

In any event, neither the USA nor NATO have responded favorably to Moscow’s avowed security interests on either the large or small scale. The US rejoinder to Moscow’s draft treaty (inclds English translation) did offer renewed dialog on some issues and the possibility of negotiating some relevant arms control agreements and confidence building measures. However, the response deferred such discussion to a Russia-NATO format, thus delaying it, and also asserted that negotiations should occur within the framework of 1990s East-West agreements and forums that Moscow now considers long-surpassed and rendered moot by Western actions over the past two decades.

With regard to NATO enlargement, the US document simply reiterates disingenuous cant about NATO’s “open door.” Additionally, the United States offered its own list of complaints to be discussed, covering inter alia Russian troop presence in Crimea, Moldava, and Georgia. This is fair enough, but the document’s closing sentence undercuts the prospect for negotiation: “It is the position of the United States government that progress can only be achieved on these issues in an environment of de-escalation with respect to Russia’s threatening actions towards Ukraine.” In other words, you stand down and then we can discuss your concerns and ours.

This offers Moscow no easy or respectable exit from the current standoff, no “golden bridge” out. The United States is offering Moscow the sole option of empty-handed and humiliating retreat. This is all that Washington thinks Moscow deserves. Of course, at this point, Moscow might find useful America’s very public presentation of “an offer they cannot accept.” How might this be viewed outside US-allied capitals (and even within some)? Might it inadvertently afford Moscow some greater political freedom to take direct action? The same might be true of perspectives on Ukranian President Zelenskyy’s hardline insistence on vacating the Minsk II promise of true autonomy for the rebel regions. (The agreement continues to enjoy strong declaratory support on all sides because it dramatically reduced the carnage of Ukraine’s civil conflict – most died prior to Minsk agreement – in the first years of the fighting.)

Moscow’s Options for Action

As stated at the outset, there’s no good reason for Moscow to seek or attempt the conquest of all Ukraine. The least demanding option suggested above would involve the transfer of very substantial amounts of armament to the rebel areas, possibly together with additional Russian “volunteers.” This would undergird a “porcupine defense”.

Most of the Russian units currently arrayed along Ukraine’s borders might then gradually withdraw, leaving behind some rapid intervention forces and a considerable number of artillery, air defense, and reconnaissance assets to buttress rebel defenses, if need be. This degree of intervention might come as a considerable relief to those led for months to expect a massive invasion – thus weakening western support for severe sanctions. Indeed, subsequent efforts to stymy the Nord Stream 2 pipeline might fracture NATO.

Complimentary Russian political steps might include a formal pledge to help defend the rebel areas against military offensives. Not likely would be recognition of these areas as independent states, as was the case with Abkhazia and South Ossetia in Georgia. Such might foreclose their reintegration with Ukraine, which Moscow prefers (although the rebel leadership might not).

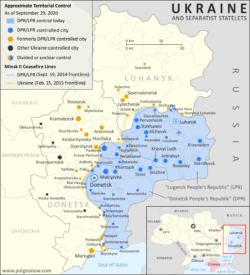

A more ambitious and less likely objective would be to help recover areas lost by the rebels since 2015 or even to extend control to the whole of Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts. (The lost areas are depicted in the map “Ukraine and Separatist Statelets,” which also shows the full extent of the related Oblasts). This larger area might prove more defensible because it would be less vulnerable to flank attack. The resulting rebel “republics” would face the rest of Ukraine on only one side. But this assumes that the rebel forces could confidently hold this expanse without a long-term large-scale influx and stationing of Russian troops (which would support the narrative of “Russian occupation.”) Obviously, this larger-scale option for Russian action would be much more demanding and costly for Moscow’s forces, and it would likely prompt US-promised sanctions.

A more ambitious and less likely objective would be to help recover areas lost by the rebels since 2015 or even to extend control to the whole of Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts. (The lost areas are depicted in the map “Ukraine and Separatist Statelets,” which also shows the full extent of the related Oblasts). This larger area might prove more defensible because it would be less vulnerable to flank attack. The resulting rebel “republics” would face the rest of Ukraine on only one side. But this assumes that the rebel forces could confidently hold this expanse without a long-term large-scale influx and stationing of Russian troops (which would support the narrative of “Russian occupation.”) Obviously, this larger-scale option for Russian action would be much more demanding and costly for Moscow’s forces, and it would likely prompt US-promised sanctions.

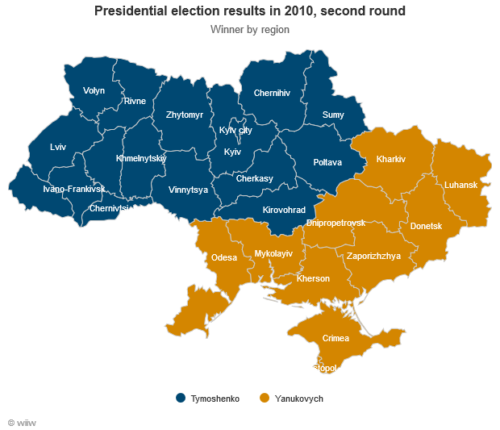

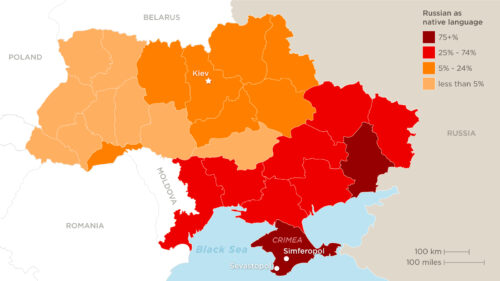

The farthest plausible limit of Russian advance would aim to occupy all of those areas of Ukraine that have a higher concentration of ethnic Russians, Russian speakers, and citizens who voted for the former president Viktor Yanukovych (who was deposed by the Euromaidan revolutionaries). (See maps below) This is not to assume that Russian invaders would be welcome in these areas, only that Moscow might hope to face less resistance there. And why might Moscow attempt such a risky gambit? To substantially increase its defensive depth – an objective that speaks directly to concerns about the advance of NATO.

Map ⇓ indicates the geographic distribution of native Russian-language speakers

Map ⇓ indicates distribution of support in the 2010 election for Viktor Yanukovych, the president deposed by the Euromaidan revolutionaries in 2014.