Charles Knight, 17 October 2022

~ James Baldwin, 1962

The comforting narrative of a dependable and stable nuclear deterrence between the US and Russia has been thrown into disarray by the War in Ukraine. This narrative, propagated widely in the years following the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, held that both the Super Powers fully appreciated that they could not “win” a nuclear battle and, therefore, would avoid direct conventional warfare, which might then quickly escalate into nuclear war. In a necessary corollary, it was thought that Russia and the US would make every effort to avoid a conventional war in Europe. Why? Because there are so many paths to escalation to nuclear war in Europe. Elsewhere in the world, US and Russian interests were more diffuse and, therefore, not so vital.

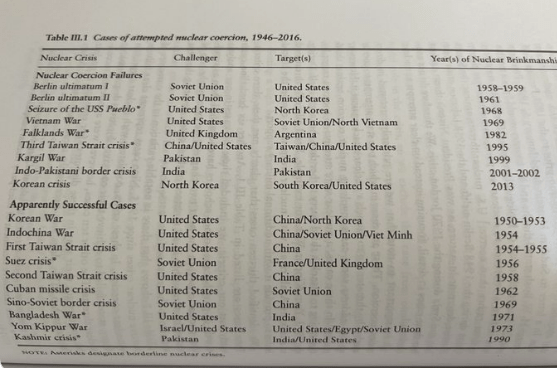

Recently Political Scientist Matt Fuhrmann posted on Twitter (@mcfuhrmann 10/10/22) a chart of “Cases of Attempted Nuclear Coercion 1946-2016.” It is from his and Todd Sechser’s 2017 book, Nuclear Weapons and Coercive Diplomacy, p. 128. Fuhrmann’s Tweet begins: “Wondering how Putin’s nuclear threats over Ukraine compare to other nuclear crises?”

In their book, Fuhrmann and Sechser list 19 cases of attempted nuclear coercion over 75 years. I use the Fuhrmann/Sechser assembly of instances of attempted nuclear coercion as a starting data point to examine what the Ukraine War might mean for the notion of a stable (mutual) nuclear deterrent between two major nuclear powers.

The Construction of a “Stable Nuclear Deterrent”

I ask the question, Is the nuclear deterrent aspect of the US/Russian relationship presently stable in any meaningfully reliable way?

Theoretically, for an effective and stable mutual nuclear deterrent, a credible capability must exist to respond to a nuclear attack with an overwhelming retaliatory attack. However, this was not the case for the Soviet Union until the end of the 1950s or the beginning of the 1960s. This meant that the US had about fifteen years following WWII in which it had relatively unrestrained nuclear options and could attempt nuclear coercion or compellence of adversaries without risking devastating retaliation by the target country.

Theoretically, for an effective and stable mutual nuclear deterrent, a credible capability must exist to respond to a nuclear attack with an overwhelming retaliatory attack. However, this was not the case for the Soviet Union until the end of the 1950s or the beginning of the 1960s. This meant that the US had about fifteen years following WWII in which it had relatively unrestrained nuclear options and could attempt nuclear coercion or compellence of adversaries without risking devastating retaliation by the target country.

The Cuban Missile Crisis marks the time when the US came to grips (for both the professional military leaders and the public) with the reality of mutually assured destruction … and thus, there was the need to invent a notion of a stable nuclear deterrent. Not that the nuclear arms race ceased after the Cuban Missile Crisis. It continued until the end of the Cold War (and has recently resumed.)

Nor did the US or the Soviet Union refrain entirely from attempting nuclear coercion. But Fuhrmann and Sechser only cite the 1969 threat by the US during the Vietnam War and the complicated multi-party threats during the 1973 Yom Kippur War as instances of attempted nuclear coercion in wars in which both the US and the Soviet Union were intensely interested parties. These should be counted as instances in which threats to use nuclear weapons locally could have escalated into a nuclear war between the great powers.

What did change after the Cuban Missile Crisis is that only a minority in the US leadership ranks believed there was a realistic chance to return to the heady days in the 1950s when it was possible to believe in the efficacy of nuclear compellence targeted at a near-peer nuclear power.

What does the history of attempted nuclear coercion tell us about the situation in Ukraine?

In this article, I discount all the instances in the Fuhrmann/Sechser list before 1960, leaving 13 cases over the 56 years from 1960 to 2016.

From those, I further remove those that do not pertain principally to conflict between the US and the Soviet Union/Russia. We then have left just 3 cases: the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, the Vietnam War in 1969, and the Yom Kippur War in 1973.

Of these three, only the Cuban Missile Crisis qualifies as a direct big-power strategic confrontation. In Vietnam and the Middle East, the US and the Soviet Union were engaged as supporters of different sides in a local conflict. It is thought that these are the sort of conflicts in which the big powers are not likely to risk all by using nuclear weaponry.

In the run-up to the Cuban Missile Crisis, each side in that dangerous strategic confrontation had deployed medium-range strategic missiles to the territories of their allies in the close vicinity (Turkey and Cuba) of their adversary. As a result, both felt that the other nuclear power had critically threatened vital strategic interests.

Leaders on both sides in that crisis had to maintain an intense rational focus to arrive at a compromise settlement that would avoid nuclear war. Yet, despite their demonstrated rationality, there were several unexpected developments during the crisis not under the leadership’s control and which could have led to disaster. (See, for instance, Michael Dobbs, “I’ve Studied 13 Days of the Cuban Missile Crisis. This Is What I See When I Look at Putin,” New York Times, 5 October 2022.)

In some important ways, the Ukraine War presents a greater nuclear risk than the Cuban Missile Crisis. Therefore, it demands even more careful rationality and restraint by Russia and the US.

By making threats to use all means at his disposal to protect the existential interests of Russia and its territorial integrity, Putin is using nuclear coercion to limit his adversary’s options in the war. However, as with most other instances of nuclear coercion, this is a highly risky tactic and inherently unstable. (See Steven Pifer, “Pushing back against Putin’s threat of nuclear use in Ukraine,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 10 October 2022, for how Putin has attempted to limit and restrain US/NATO support for Ukraine by repeated reference to his military nuclear options.)

Several things make the Ukraine War nuclearly fraught:

- Putin has annexed several Ukrainian oblasts, effectively making them into vital Russian territorial interests to defend from the NATO-backed challenge. He has effectively created a situation that fits the criteria in Russian military doctrine for using nuclear weaponry. I assume he knows what he was doing in this regard. His views on the role of nuclear forces in defending Russian territory are clear.

- The very success to date of the Ukrainian defense increases the perceived “need” for Moscow to reach for high-risk military options.

- This is a war in Europe, precisely the sort of conflict that the Soviet Union and the US learned to avoid after the Cuban Missile Crisis. We are lucky that the Soviet Union and the US learned that lesson. It helped us to survive the Cold War. Unfortunately, with the launch of the Ukraine War, that wise restraint has been destroyed. There are so many ways wars in Europe can go wrong: too many nations very near each other that have nuclear weapons — most all with complex histories and cross-cutting webs of interests. With human emotions added into the mix, any war in Europe can easily and quickly escalate into irrational levels and types of violence.

What NATO and the US Must Do to Avoid Escalation to Nuclear War?

Some things can be done by the US or NATO nations to reduce the probability that Putin will order the use of nuclear weapons:

- The US and NATO must make sure Putin and other Russian leaders know that there are realistic “exit ramps” from their war effort. Likewise, the Kremlin must know there are options to end this war that avoid oblivion.

- As Kennedy smartly pursued talks behind the scenes with the Soviets during the Cuban Missile Crisis, so must Washington pursue similar discussions with the Russians now. Domestic political pressures will necessitate that these talks be secret. They may not produce serious negotiations soon, but they serve to maintain a relationship and take psychological pressure off the Kremlin leaders that might otherwise incline them to use nuclear weaponry.

- It is essential to make clear to the Kremlin a willingness to lift specific categories of economic sanctions when a negotiated war settlement is achieved.

- The US has shown some wise restraint in the qualitative aspects of its substantial military support of Ukraine. This support has included not only ordnance and some sophisticated equipment but also superb battlefield intelligence. Nevertheless, the US must continue to ensure that no US service people become directly engaged in the fighting or are in harm’s way on the ground, sea, and air in the vicinity of the war. Deaths of US soldiers in this war could result in intense domestic pressure on Washington to retaliate against Russia, risking rapid escalation.

- The US must resist suggestions that it supplies Ukraine with longer-range weaponry which could hit targets deep inside Russia. Moreover, Washington must restrain impulses to involve its military forces in the air or naval interdiction of Russian military platforms.

To return to the central question about the stability of nuclear deterrence in Europe between Russia and the US/NATO, it should be clear that any remaining mutual deterrence is presently highly fragile. It lacks a stable platform of shared strategic understanding.

And to the extent that we would rely on human rationality as a factor in deterrence, we must realize that rationality only goes so far. Indeed, presently, a very short way. Reflect for a moment on the recent history of big-power leadership. The US just went through four years with Donald Trump as commander-in-chief. It should be clear by now that neither was he inclined toward disciplined rationality nor did he have the most basic understanding of the limited “usefulness” of nuclear weapons. Furthermore, he did not demonstrate any interest in learning about such.

Putin’s degree of commitment to and capacity for rationality in his leadership of Russia remains unknown. His recent decisions about Ukraine do not give one confidence in that regard. Joe Biden is an old Cold Warrior, and no doubt learned a few things about what was safe to do and what wasn’t. However, he is famous for impulsive statements in public. We must hope he is more deliberate and careful in the war room.

Nonetheless, the historical record of national leadership informs us that we can not rely on rationality to carry the day, especially in the pressure cooker of war. Presently the world is utterly vulnerable to any failure of Biden or Putin to stop short of direct warfare between their respective military forces! The paths on which that failure could happen multiply the longer the war continues.

The US/NATO war effort in Ukraine must remain deliberately limited. Beyond that, we must resist the usual war fevers (beset with visions of victory over evil) that take nations toward total war.